In a world where the instant image predominates and where immediacy has become the dominant visual language (from social media to urgent photojournalism), long-term photographic series represent a necessary counterweight. Faced with the vertigo of the fleeting, these types of projects propose a different temporality: a slow, constant gaze, committed to deep observation and the evolution of the subject. They are, therefore, a form of cultural resistance to the superficial consumption of images.

The importance of a long-term photographic series lies, first and foremost, in its ability to construct a complex and evolving visual narrative. Where a single image can insinuate or suggest, a series allows a story to unfold, unravel layers of meaning, and reveal processes of transformation. Each photograph is not an end, but a fragment of a larger whole. In that sense, a series is like a symphony composed of movements, or a novel written in images: its strength lies in the whole, in the relationships between the parts, in the rhythm, in the variations and repetitions that the viewer discovers.

This narrative complexity is clearly revealed in works such as W. Eugene Smith’s The Country Doctor, one of the first photojournalistic series to explore the daily life of a rural doctor in the United States with unprecedented emotional depth. Over weeks of living together, Smith documented not only clinical procedures but also the humane gestures, fatigue, vocation, and loneliness of his subject. The series did not aim to depict a decisive moment, but rather to construct a sustained atmosphere, a sensitive experience where photography was no longer a distant witness, but rather part of the event.

W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith

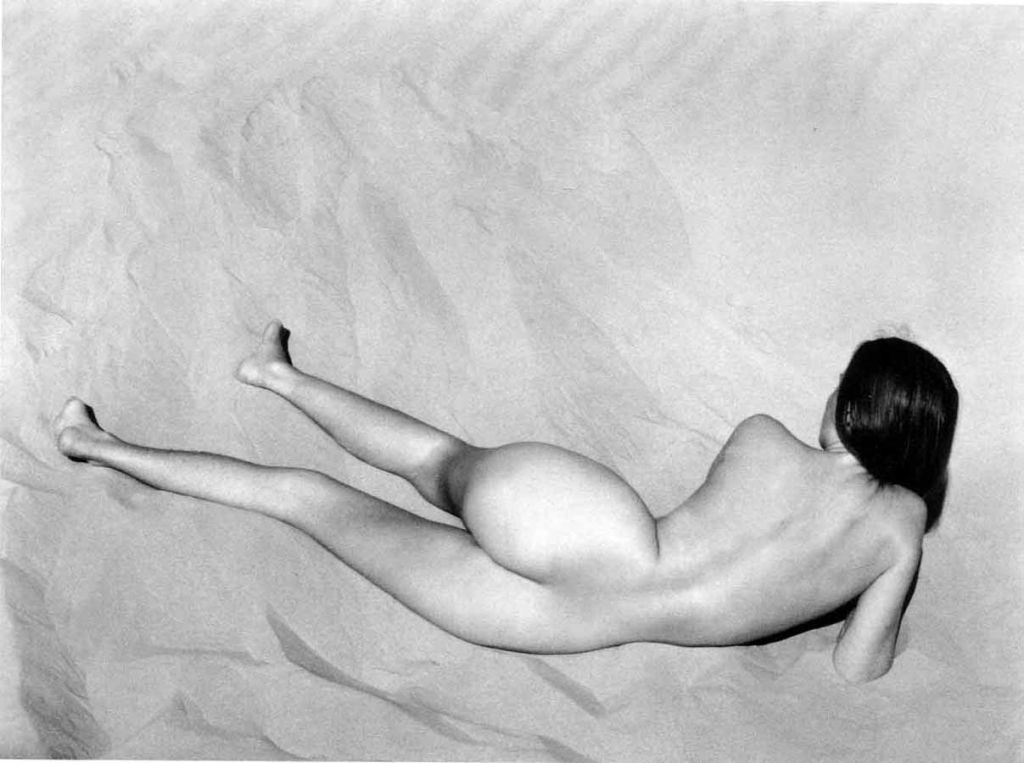

Similarly, Edward Weston’s Nudes demonstrates how an extended series can transform a traditional subject (the human body) into a formal and philosophical exploration. For over a decade, Weston photographed bodies with a sculptural, abstract gaze, eliminating the anecdotal to focus on light, texture, and form. This continuity allowed him to refine his visual language, moving from simple recording to the systematic study of the aesthetic possibilities of anatomy. Rather than a single iconic nude, the series builds a coherent corpus where each image dialogues with the previous one, and where consistency becomes depth.

Edward Weston

Edward Weston

Edward Weston

The extended period offers not only a thematic evolution, but also an evolution of the visual language itself. As the photographer returns to his subject, he can experiment with formal variations: changes in light, composition, framing, color, and the type of relationship with the subject. This continuity opens up the possibility of an artistic evolution that is not always evident in short-term projects. Furthermore, series allow for the construction of a richer visual grammar, where each image interacts with the others, creating resonances, tensions, or harmonies that the viewer discovers over time.

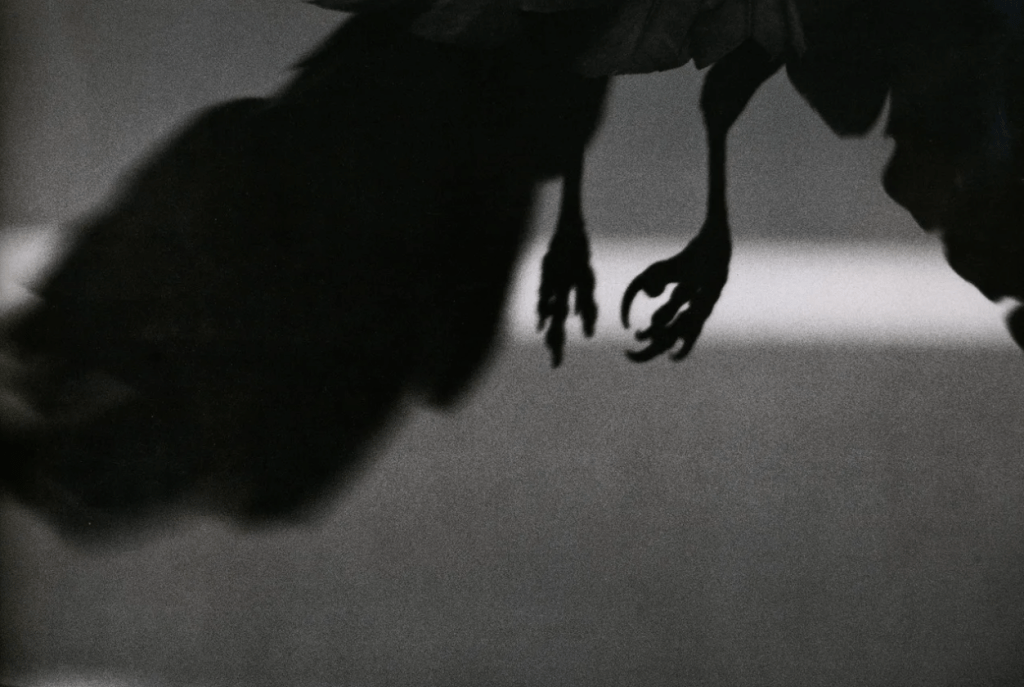

Another paradigmatic example of this commitment to transformation, both of the subject and the gaze, is Masahisa Fukase’s Ravens. This series, created after a painful separation, became a visual meditation on grief, loss, and loneliness. For years, Fukase photographed crows in gloomy landscapes, with compositions laden with symbolism and emotional darkness. The reiteration of the motif, far from being monotonous, constructs a narrative where the bird becomes a visual echo of the author’s own inner state. The series is not only a documentation of birds, but a self-portrait in disguise.

Masahisa Fukase

Masahisa Fukase

Masahisa Fukase

Photographing something or someone over an extended period entails a form of responsibility: it’s no longer a matter of a gaze that extracts or exploits a photogenic moment, but rather a sustained relationship, where trust is built, stories are shared, and empathy is generated, which is translated into the image. This ethical dimension is especially relevant in projects involving vulnerable communities, personal processes, or life changes. In many cases, continuity allows the photographer not only to observe, but to become involved, to be part of what they document, and that involvement transforms the image into something deeper.

A series like Josef Koudelka’s Exiles, composed over two decades, reflects this approach. In it, the Czech photographer (after fleeing what was then communist Czechoslovakia) travels through different European countries, documenting solitary scenes, absent faces, displaced figures, and landscapes filled with melancholy. Koudelka doesn’t portray exile as a specific story, but rather as an existential condition: the series is not a chronicle of physical displacement, but of emotional uprooting. Only time could allow for this accumulation of symbols, gestures, and inner geographies that construct such a profoundly coherent and universal work.

Josef Koudelka

Josef Koudelka

Josef Koudelka

These series are not limited to documenting the present, but rather build bridges between past, present, and future, and often become a reference for researchers, artists, and future viewers. In the field of contemporary art, many of the most influential works of the 20th and 21st centuries have been the result of prolonged photographic processes. This choice is not only linked to a documentary intention, but also to a conceptual reflection on time, repetition, memory, and permanence. The long-term series, then, becomes a conscious artistic gesture: a way of challenging the here and now, of working against the obsolescence of the image, of creating works that develop as processes rather than final products.

By structuring a visual story in multiple stages, the photographer offers the viewer a more immersive and participatory experience. They must pause, compare, interpret, recall previous images, and anticipate what’s to come. The series demands active attention. It doesn’t simply impact, but proposes a way of reading that is more akin to critical thinking than passive visual consumption. And that, in a world saturated with images, is an essential form of visual education.

The long-term photographic series is not just a technique or a format; it is a working philosophy, a way of seeing, of narrating, of engaging. It is a commitment to depth over surface, to duration over the instant, to process over immediate result. And in that commitment lies its power, its beauty, and its cultural, historical, and artistic relevance.

The importance of these series lies not only in their final result, but in the journey they entail: an exercise in the photographer’s fidelity to their subject, a test of endurance in the face of the vagaries of immediate interest, a way of thinking with the camera over time. The photographer who decides to commit long-term to a story, a subject, or a place adopts an ethic of permanence. They don’t just arrive, shoot, and leave: they return, observe, listen, coexist. They become involved. And that involvement inevitably seeps into the images, giving them a density that instantaneousness cannot achieve.

Long-term photographic series not only enrich contemporary visual language, but also teach us to look differently. They teach us that time is not the enemy of the image, but its greatest ally. That art is not always about the immediate or the novel, but about the ability to sustain a question, to inhabit a space, to coexist with a history.

At a time when everything tends to disappear at the speed of a scroll, looking back at these projects (dense, complex, enduring) is also an act of relearning: a way of relearning how to see, understand, and feel through images. Because, ultimately, every great photographic series speaks not only to the world it depicts, but also to the way we choose to be in it.

Deja un comentario