Paolo Roversi was born on September 25, 1947, in Ravenna, a small city in northern Italy known for its Byzantine history and artistic richness. This profound cultural atmosphere significantly influenced his visual sensibility from an early age. It was during a family vacation in Spain, when he was seventeen, that he took his first photograph with a Kodak camera. The experience of capturing an image quickly became a persistent fascination.

His first professional contact with photography came when he began working as an apprentice in the studio of local photographer Nevio Natali. Under his tutelage, Roversi began to learn the technical fundamentals of the craft in developing, lighting, and composition. During this period, his training was classical and rigorous, based on analog processes, which laid the foundation for his distinctive style. In 1970, driven by a desire to explore new creative frontiers, Roversi moved to Paris. The city, then the epicenter of fashion and art, offered him the ideal environment to develop a career as a professional photographer. Although his early years in Paris were marked by struggle and economic uncertainty, perseverance and his emerging style soon led him into the circles of fashion and advertising.

From his beginnings in the 1970s, Roversi emerged as a photographer who responded not to the dictates of the market, but rather to a personal need to create images that told intimate and emotional stories. His arrival in Paris in 1970 coincided with a time of great cultural and aesthetic fervor in Europe, which offered him fertile ground for experimentation and growth.

His first years in the French capital were not easy. Like many young photographers, he had to face a competitive environment dominated by established names such as Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, and Sarah Moon. To survive, he did laboratory work, technical assistance, and small collaborations with advertising agencies. However, this period also allowed him to observe, learn, and begin to develop his own visual voice.

His first major professional achievement came in 1974, when renowned art director Peter Knapp of Elle introduced him to the world of fashion publishing. Through him and other contacts, Roversi began working for magazines such as Marie Claire, Depeche Mode, and later Vogue Italia. His connection with the latter magazine became one of the most fruitful partnerships of his career, thanks to the visionary eye of Franca Sozzani, who gave him complete creative freedom to develop unusual photo essays.

During the 1980s, Roversi consolidated his unique style. Instead of following the more commercial path of fashion photography, he opted for an introspective, poetic, and experimental approach. During this time, he stopped using 35mm or medium-format cameras and adopted the large-format 8×10-inch camera. This decision had aesthetic implications. The large camera, with its slow framing and focusing process, allowed for a more intimate relationship with the subject and required an attentive presence from the photographer.

It was also in this decade that Roversi discovered Polaroid 809 instant film, which would become one of his signature styles. The film, originally used for exposure tests, offered a soft texture, desaturated colors, and a level of detail that perfectly suited his pursuit of the intangible. Roversi transformed this technique into an art form: his Polaroid portraits seemed to emerge from a reverie, suspended between the material and the spiritual.

His studio, located on Rue Paul Fort in Paris, unlike commercial studios filled with assistants and machinery, Roversi’s space was intimate, almost silent. There, without rush or external pressure, he conducted sessions that could last for hours. The ritual consisted of setting the scene precisely: natural light or a single soft source, models without exaggerated makeup or forced poses, a neutral background, and a focus on expression rather than attire.

Over the years, Roversi worked with designers who shared his artistic sensibility. With Romeo Gigli, for example, he developed campaigns that explored romanticism and melancholy. With Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garçons, he immersed himself in an Eastern aesthetic. Later, he collaborated with brands such as Dior, Valentino, Alberta Ferretti, Lanvin, Giorgio Armani, and Hermès, among others. Although these projects fell into the field of advertising, Roversi always knew how to preserve his style, avoiding marketing clichés.

One of the most notable aspects of his career is his ability to transform models into muses, but also into collaborators. Unlike the object-oriented approach that predominates in fashion, Roversi built a relationship with them based on trust, introspection, and listening. Models such as Guinevere van Seenus, Natalia Vodianova, Kirsten Owen, Stella Tennant, and Tilda Swinton returned to his studio again and again, seduced by the calming and profound atmosphere of his sessions.

In addition to fashion photography, Roversi ventured into artistic and editorial portraiture. He portrayed figures from the arts, film, and music, always following the same logic of inner search. His portrait of Robert Frank, for example, or his series of actors and actresses for Another Magazine and Vogue Hommes, demonstrate his interest in stripping the subject of public masks and revealing something essential.

Over time, his influence became transversal. While he never embraced digital styles or passing fads, Roversi remained a reference for both young photographers and publishing houses. In the 2010s, he worked with new generations of designers and artists, without losing his analogical and reflective essence. In an industry dominated by speed, mass image consumption, and digital immediacy, Paolo Roversi resisted with a contrary approach: look slowly, look deeply, look with devotion.

One of his recent projects was his participation as photographer for the prestigious 2020 Pirelli Calendar, entitled Looking for Juliet. In this project, Roversi reinterpreted the Shakespearean figure of Juliet through multiple women who embodied different facets of the character. The result was a lyrical calendar, laden with symbolism, a complete departure from the sensual and commercial tone of other editions, and which reaffirmed his position as an absolute master of portraiture.

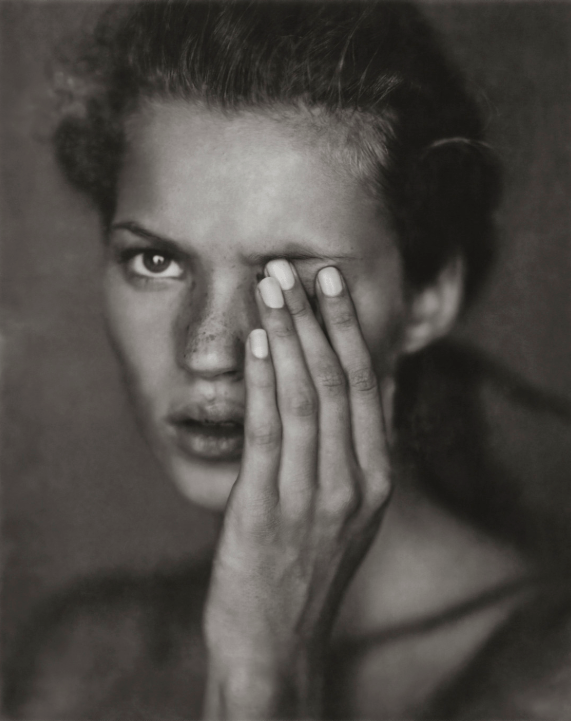

Today, with more than five decades of experience, Paolo Roversi continues to work in Paris, faithful to his studio, his large-format cameras, and his silent search for the essential. Paolo Roversi’s work is one of the most personal and poetic in fashion photography. Since he began working with a large-format camera and Polaroid film, he distanced himself from the commercial path followed by many other photographers. While the industry sought bright, fast, and modern images, Roversi opted for the opposite: the slow, the soft, the introspective. His photography isn’t just about showing clothes or faces. He doesn’t seek perfect beauty, but a deeper, emotional, and sometimes melancholic truth. He is interested in capturing that moment when someone lets their guard down, when they stop posing.

One of the most recognizable aspects of his style is his use of light. For him, light is not just a technical resource, but something alive. He says light is like a spirit that caresses the subject and reveals them. Many of his photographs have that soft, diffuse glow that seems to come from another time. Often, shadows and out-of-focus are an essential part of the image. He doesn’t correct «mistakes»; he embraces them, because he believes that imperfection is also the most human.

His portraits have something ancient and modern at the same time. Sometimes they are reminiscent of paintings by the great masters of the Renaissance or Baroque. Other times, they seem like visions of the future. He uses simple backgrounds, almost always gray or black, which make the subject stand out more. The colors are desaturated, subdued, as if they are slowly fading away. The poses are soft, never forced. The gestures seem to emerge naturally.

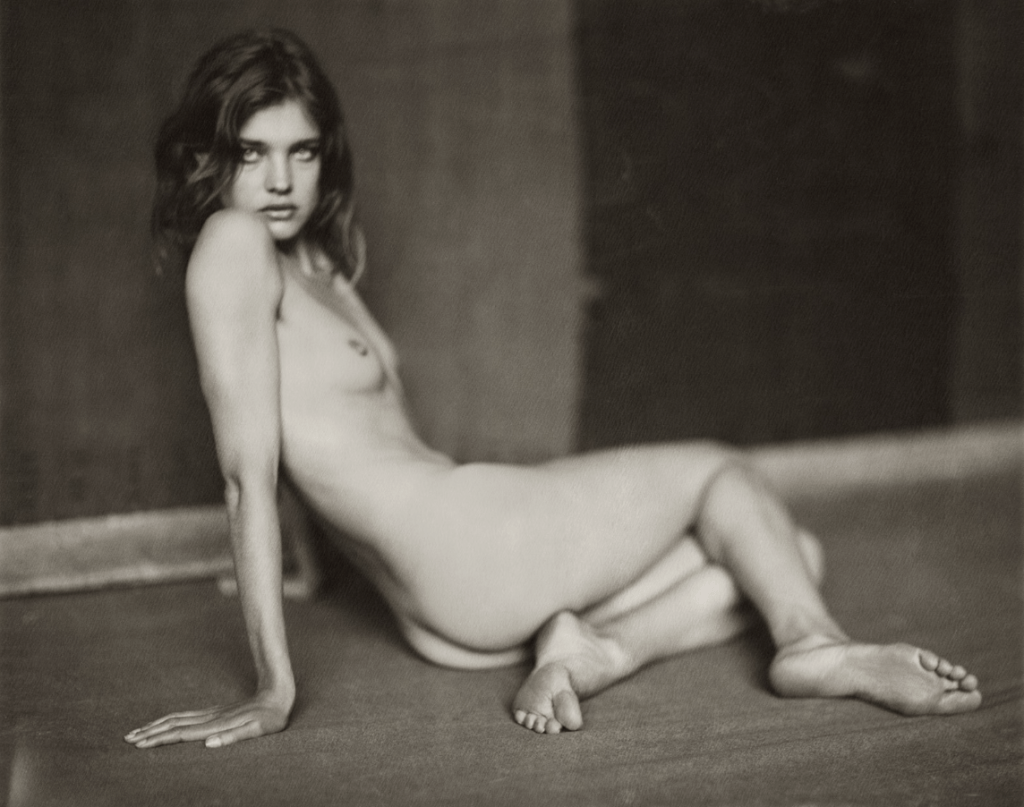

One of the central themes of his work is the feminine. Over the years, he has photographed many women, always from a delicate, respectful, and never sexualized perspective. Rather than turning them into objects of desire, he presents them as enigmatic, profound beings, full of presence. In his photographs, a woman can appear like a Renaissance muse, a time traveler, or a figure from a fairy tale that needs no explanation.

He has also explored the nude. In his book, Nudi, for example, the body appears as a fragile, silent, exposed place. There is no provocation, there is contemplation.

For Roversi, fashion is not the center of the image, but a language. The dress is an extension of the character. Sometimes it hides, other times it reveals. It never imposes. He himself has said that he is not interested in photographing the garment, but rather what the person feels when wearing it. That’s why he works so much with designers who value poetry in clothing, such as Yohji Yamamoto, Comme des Garçons, and Romeo Gigli.

Although his images appear in magazines and fashion campaigns, Roversi does not work to sell. His intention is not commercial, but artistic, even when it comes to commissioned works, he manages to imprint his style on them: intimate, soft, mysterious.

Throughout his career, he has photographed both unknown models and major stars. But his way of seeing remains unchanged. Whether a young debutante or a global celebrity, Roversi portrays them with the same calm and depth. He doesn’t seek fame or spectacularity. He seeks humanity. In times when photography has become increasingly digital, rapid, and artificial, Paolo Roversi remains faithful to film, to the big camera, to the darkroom, to error. To everything that involves slowness, waiting, and dedication.

Published Books

Paolo Roversi has published several books that compile his most representative works. Among the most notable are

- Libretto (1989): His first book, focusing on the minimalist elegance of the female form and fashion.

- Nudi (1999): A collection of poetic nudes, where the body is treated with an almost spiritual delicacy.

- Studio (2008): A look at the creative process inside his Paris studio, revealing the artisanal nature of his photographic method.

- Secrets (2013): A book published on the occasion of his exhibition in Paris, featuring intimate portraits and visual meditations.

- Storie (2017): A retrospective book that brings together decades of work, with an emphasis on visual narrative rather than chronology.

- Paolo Roversi: Studio Luce (2020): A catalog of the exhibition at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, offering a curatorial overview of his entire career.

Deja un comentario