Since the dawn of photography, the self-portrait has been a privileged medium for personal exploration and representation of the self. Unlike the traditional portrait, the self-portrait adds an introspective, performative, and even philosophical dimension: what does it mean to look at oneself from the outside? How is an identity constructed in front of the camera, and for whom? These questions permeate the work of numerous photographers who have used their own image as a field of aesthetic, conceptual, and emotional experimentation.

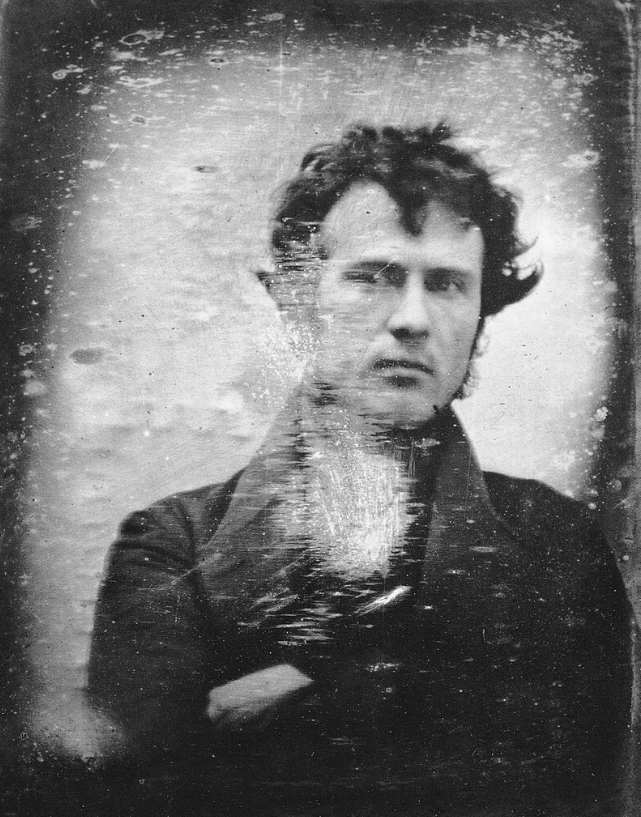

From the daguerreotype to contemporary selfies, the self-portrait has been a constant in the history of photography. The first known self-portrait is attributed to Robert Cornelius in 1839, just a few months after the medium’s official invention.

In its beginnings, the self-portrait responded to a technical and practical need: photographers experimented with their equipment and chemical processes, using themselves as models. However, this practice soon acquired a symbolic dimension: the author who represents himself takes control of his image, constructs a narrative of himself, and engages in dialogue with his time.

In the 20th century, with the rise of conceptual art, psychoanalysis, and gender studies, the self-portrait became a powerful tool for questioning identity. It was no longer just about seeing oneself, but about interpreting oneself, disguising oneself, unfolding oneself, hiding oneself, and exposing oneself.

On a technical level, the self-portrait involves a high degree of planning and control. Unlike traditional portraiture, the photographer not only operates the camera but also occupies the space in front of it. This entails technical challenges that have evolved over time.

In the analog era, photographers used timers, remote shutter releases, mirrors, and tripods to compose their images. Precision was essential: there was no way to check the result until development. In this context, framing, lighting, and posing had to be carefully planned. Today, with digital cameras and smartphones, immediacy has completely transformed this experience.

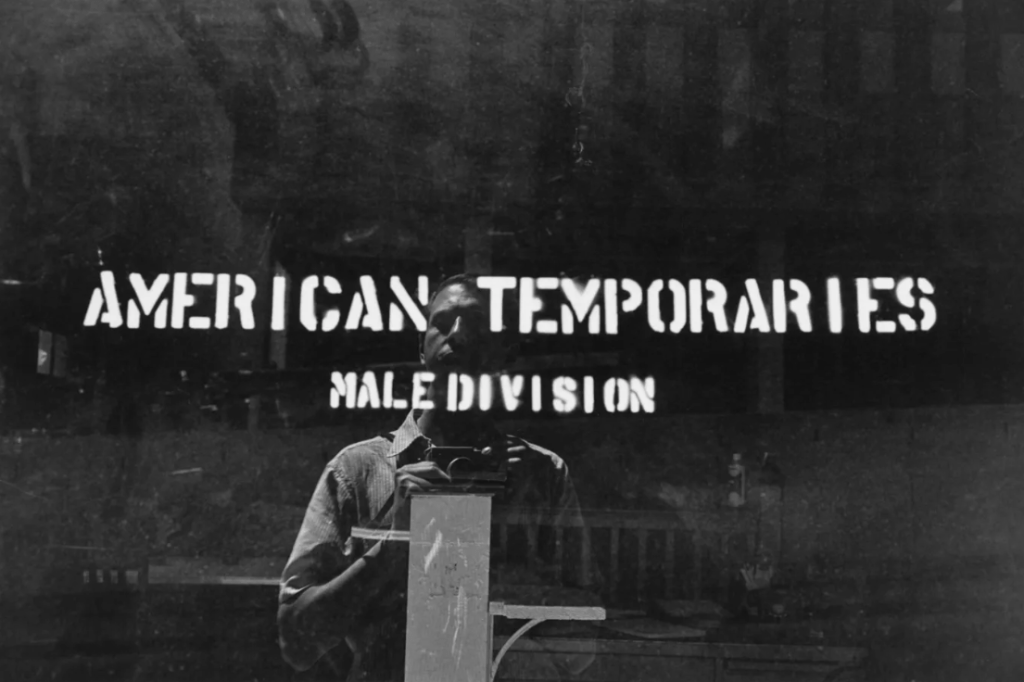

Lee Friedlander, an American photographer born in 1934, revolutionized the self-portrait genre by including himself in his own images in an indirect, fragmentary, and often humorous way. Far from the drama or introspection typical of the classic self-portrait, Friedlander chose to appear in reflections, projected shadows, silhouettes on glass, or metal surfaces.

Lee Friedlander

His Self Portrait series (1970) is emblematic: Friedlander accidentally appears in shop windows, rearview mirrors, shadows elongated by the sun, or impossible framings. Far from dominating the scene, his figure seems trapped by it, as if the camera had surprised him.

Rather than presenting himself as the protagonist, Friedlander hides in the landscape, irreverently inserting himself into the everyday. This constitutes a subtle critique of the photographic ego: his work does not contain a quest for heroism or an existential statement, but rather an ironic affirmation of the photographer’s presence as part of the world he observes. Friedlander proposes a modest and playful conception of self-portraiture, where the self does not dominate the frame, but rather dissolves into it.

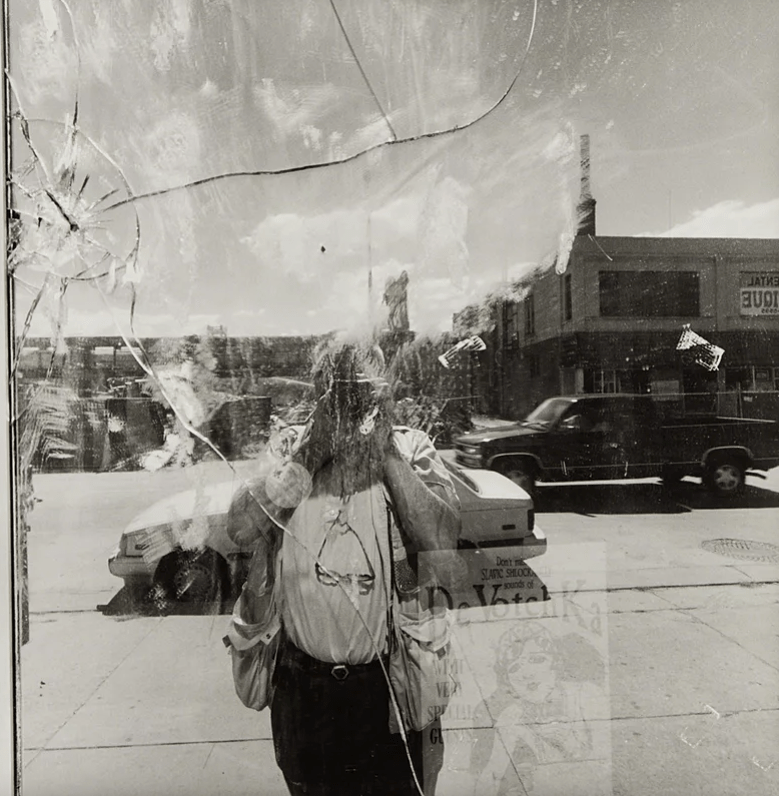

Lee Friedlander

Lee Friedlander

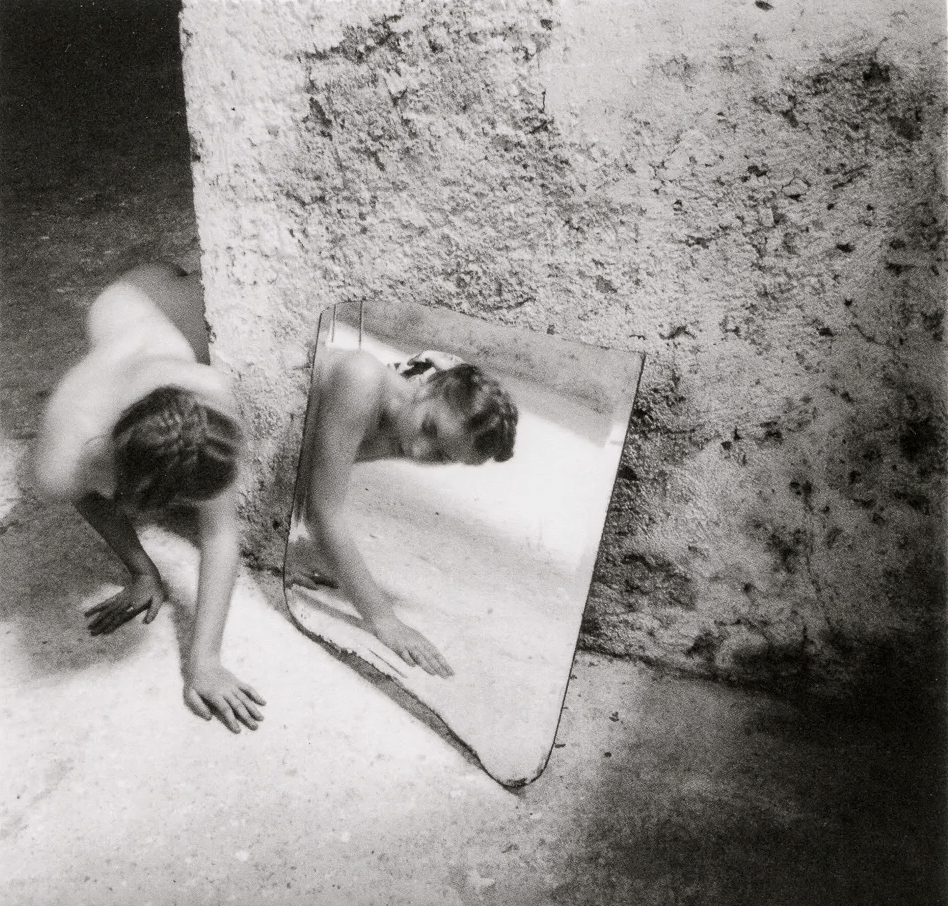

Few artists have embodied the symbolic dimension of self-portraiture with such intensity as Francesca Woodman. Born in 1958 and tragically deceased in 1981, Woodman produced a succinct, concentrated, and deeply personal body of work, in which the body (almost always her own) appears in a constant process of dematerialization, disappearance, or transformation.

Unlike the narcissistic exposure often associated with self-portraiture, Woodman portrays herself from an ambiguous and poetic place. Many of her photographs were taken in abandoned houses, ruined rooms, or dilapidated domestic spaces. In them, her body merges with the walls, is hidden behind veils, dissolves in movement, or hides behind objects. There is no affirmation of identity, but rather a play of absences: her image always appears on the verge of disappearing.

In her self-portraits, Woodman does not regard herself as an object of desire, admiration, or power. Rather, her body is a translucent symbol, a vulnerable medium for discussing fragility, desire, confinement, femininity, and death. The use of long exposure and black and white contribute to this spectral aesthetic. In her visual universe, photography captures not an essence, but a shadow, a trace. What is most remarkable about her work is that, despite her youth, Woodman achieves a symbolic maturity and emotional intensity rarely seen.

Francesca Woodman

Francesca Woodman

Francesca Woodman

Francesca Woodman

The case of Vivian Maier is one of the most fascinating of the 21st century. A nanny by profession, self-taught, and reclusive, Maier produced thousands of negatives without displaying virtually any of them during her lifetime. Her archive was discovered by chance in 2007, shortly before her death. Since then, her work has generated enormous interest for its quality, mystery, and visual power.

Maier photographed streets, children, the elderly, urban scenes, and also herself. Her self-portraits are numerous, though rarely direct. Like Friedlander, she appears in reflections of shop windows, projected shadows, glass, and puddles of water. But unlike him, Maier’s emotional tension is more intense.

In many of these images, Maier holds her Rolleiflex camera at chest level. Her face appears reflected, serious, distant, yet deeply aware of the image she is constructing. There is no coquettishness or drama. There is something melancholic and stoic, as if the image were her most intimate refuge.

Through self-portraiture, Maier constructed a silent, almost secret identity. Her images, many decades before the era of Instagram, represent a radical reflection: is it possible to take a self-portrait without seeking visibility? In a world that prizes exposure, Maier chose to see without being seen, to leave traces without names.

Her case challenges the notion of self-portraiture as an act of affirmation. For Maier, the self-portrait is a trace of passage, a proof of existence, a visual cartography of anonymity.

Vivian Maier

Vivian Maier

Vivian Maier

The self-portrait in photography is, above all, an act of visual introspection. Unlike other genres, its power lies not only in what it shows, but in what it provokes: an open question about identity, the body, the gaze, and the passage of time. Photographing ourselves goes far beyond recording a face or a posture. It is constructing a representation that, although seemingly concrete, will always be ambiguous. The self-portrait forces us to look at ourselves from the outside, to observe ourselves as another.

Over time, this genre has evolved from mere technical experimentation to an aesthetic and conceptual tool laden with meaning. It can be an intimate gesture or a political act, a form of testimony or a camouflage strategy. Self-portrait doesn’t always seek to define itself; often, its value lies precisely in the opposite: in suggesting, in concealing, in leaving room for doubt. Therefore, each self-portrait is also a mise-en-scène. The person in front of the camera, even if it’s the same person behind it, becomes a character. The camera, as a silent witness, records both what is intended to be shown and what inevitably escapes.

In times of overexposure, where the personal image circulates constantly and at an accelerated pace, the artistic self-portrait becomes a resistance to the automatism of the click. It is an act that demands pause, intention, and reflection. It’s not about generating yet another image, but rather using that image to say something, even if it cannot be said in words. It becomes a way of thinking with the body, with gesture, with light, with framing.

A self-portrait can take many forms: it can be a reflection, a shadow, a blurred silhouette, a fleeting apparition in the midst of everyday life. Sometimes the face is hidden, displaced, fragmented. Other times, it is the center of attention. Each compositional decision constructs a message about how one lives, feels, and understands one’s own identity. Thus, the self-portrait becomes a tool for questioning conventions, exploring emotions, narrating invisible experiences, or simply affirming a presence.

For all these reasons, the self-portrait should not be understood as an egocentric or banal gesture, but rather as one of the richest forms of visual expression. It is a crossroads between the private and the public, between the ephemeral and the permanent. Taking a self-portrait, in the end, is not just about seeing oneself, but about daring to be an image, with all that this implies: risk, contradiction, beauty, and truth.

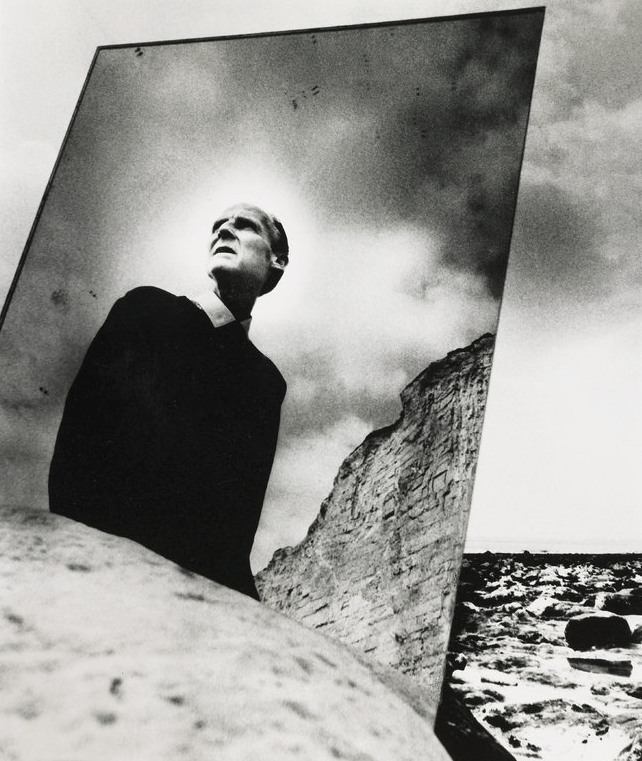

Bill Brandt

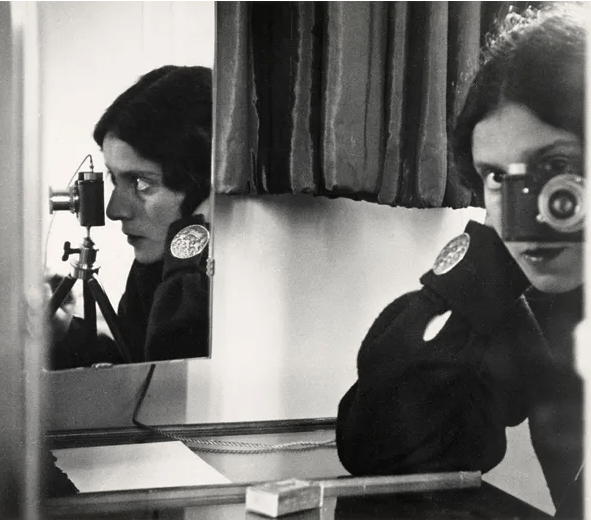

Ilse Bing

Miss Aniela

Deja un comentario