Bill Brandt was born on May 2, 1904, in Hamburg, Germany, as Hermann Wilhelm Brandt. His childhood was spent in a wealthy family of German and English descent. His father, a Hamburg banker, was stern and traditional, while his mother, of British origin, was more free-spirited, though distant. This blend of cultures would profoundly influence Brandt’s visual sensibility.

During World War I, being the son of a German and English father in Germany made him a target of ridicule and suspicion, experiences that left a deep mark on him. In 1920, he contracted tuberculosis, an illness that led him to spend several years in hospitals. It was in these isolated environments that he began to develop an interest in art and literature, reading authors such as Kafka, Thomas Mann, and Goethe. It was also there that his first contact with photography arose through illustrated magazines and medical portraits.

In the mid-1920s, having partially overcome his illness, he moved to Vienna, where he began working as an assistant to the photographer Grete Kolliner, specializing in portraits. Later, he went to Paris and there met the legendary photographer Man Ray, who accepted him as an apprentice. This encounter would prove decisive for the young Brandt, as it allowed him to learn the techniques of surrealism, the play with light and shadow, and the creative use of framing. Under Ray’s influence, his outlook became more introspective and poetic.

In 1933, at the height of the rise of Nazism, Brandt left Germany for good and settled in London. Although he adopted British nationality, he maintained an inner distance from any fixed identity throughout his life. This ambiguity would become evident in his work.

Bill Brandt’s career spans more than four decades of active and versatile photographic production and constitutes one of the most influential bodies of work in 20th-century photography. His trajectory cannot be understood as a continuous line, but rather as a sequence of stages profoundly marked by both formal and thematic transformations. Each of these phases responds to a different quest: from social documentary to expressionist experimentation, from psychological portraiture to the abstract nude.

After arriving in London in 1933, Brandt began to explore everyday life in British society. In a time of severe social and economic divisions, he found powerful visual material in class contrasts. His approach was not that of orthodox photojournalism, but that of a silent, almost invisible observer, who used the camera as an instrument of interpretation.

In The English at Home (1936), his first photography book, he presented images of bourgeois and working-class homes, portraying both the tea rituals in ornate drawing rooms and the austere routines of working-class housing in the north of England. His approach was influenced by the work of humanist photographers such as August Sander and Brassaí, but also reflected the literary vision of Henry James and George Orwell.

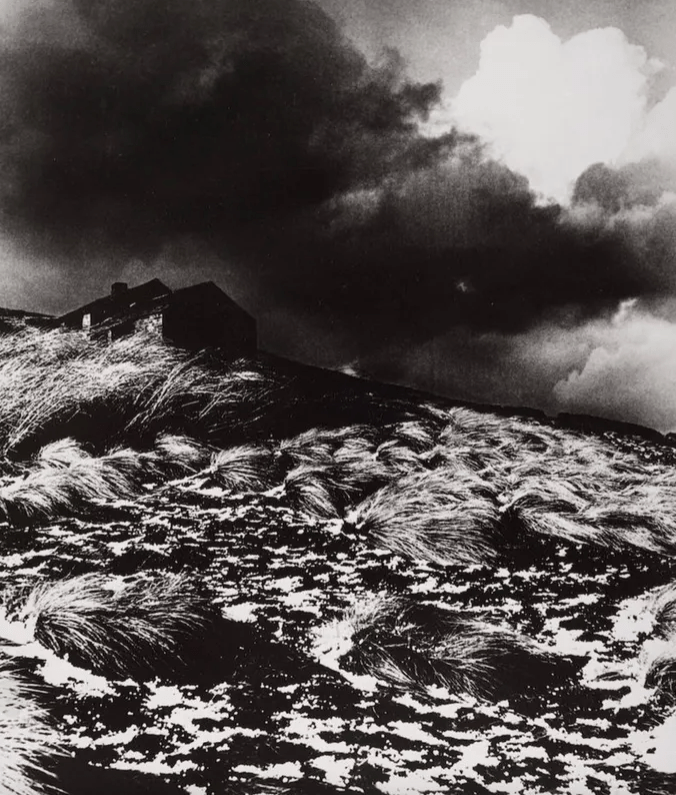

Shortly after, in A Night in London (1938), he adopted a freer and more atmospheric approach. Here, the city becomes an expressionist stage, a space for the unexpected, the melancholic, the theatrical. Long exposures and the use of contrasting black and white reveal a nocturnal city somewhere between the real and the fantastic. This work established him as a visual chronicler of the invisible: what happens on the margins of wakefulness, in deserted streets, in private interiors.

With the outbreak of World War II, Brandt turned to documenting the conflict from a deeply human perspective. He worked for the British Ministry of Information, but also contributed to illustrated magazines such as Picture Post and Harper’s Bazaar. He didn’t limit himself to capturing scenes of destruction: he focused his lens on the intimate resilience of citizens, on their capacity to adapt to disaster.

Images of families sleeping in subway stations transformed into air-raid shelters have become icons of the era. In them, Brandt captured not only a historical event, but also a moment of profound shared humanity. The scenes are carefully composed, with a clear emotional meaning.

Despite the technical limitations of the time, Brandt achieved stunning visual effects through his deliberate use of deep shadows and diagonal compositions. These stylistic choices, far from hindering understanding, enrich the emotional content of the photographs. Documenting the war, for Brandt, was not simply about showing its consequences, but about expressing the psychological state of an entire country in crisis.

At the end of the war, Brandt moved away from social reportage to embrace a more subjective and personal form of photography. This shift coincided with a growing interest in artistic portraiture, especially of writers, poets, and playwrights. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, he photographed some of the most important names in British and international culture: Graham Greene, Ezra Pound, Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, Dylan Thomas, Virginia Woolf, among many others. What is notable about these portraits is their departure from the classical style. Brandt avoided formal poses and conventional lighting. He preferred backlighting, harsh shadows, and low or very high angles.

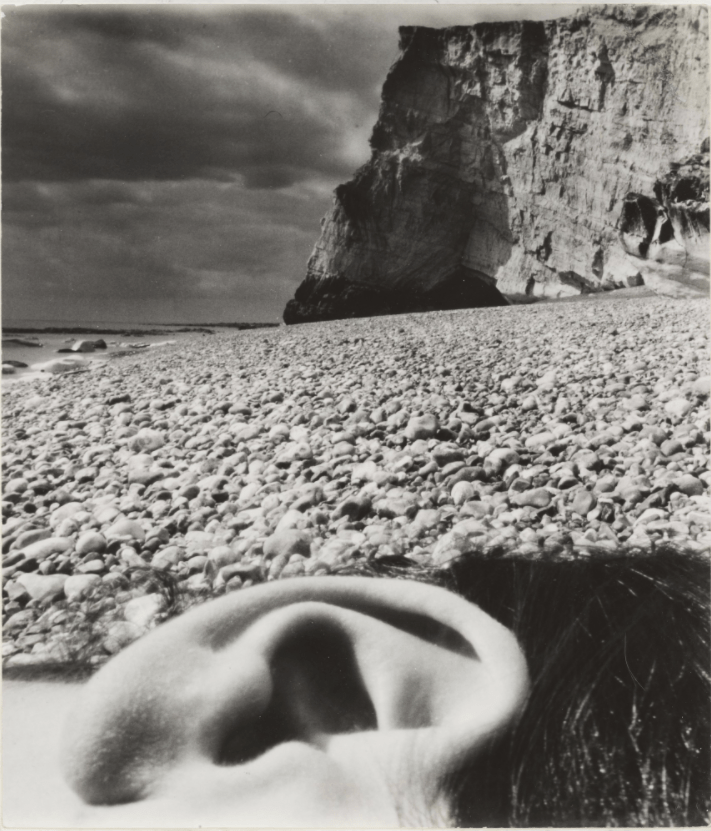

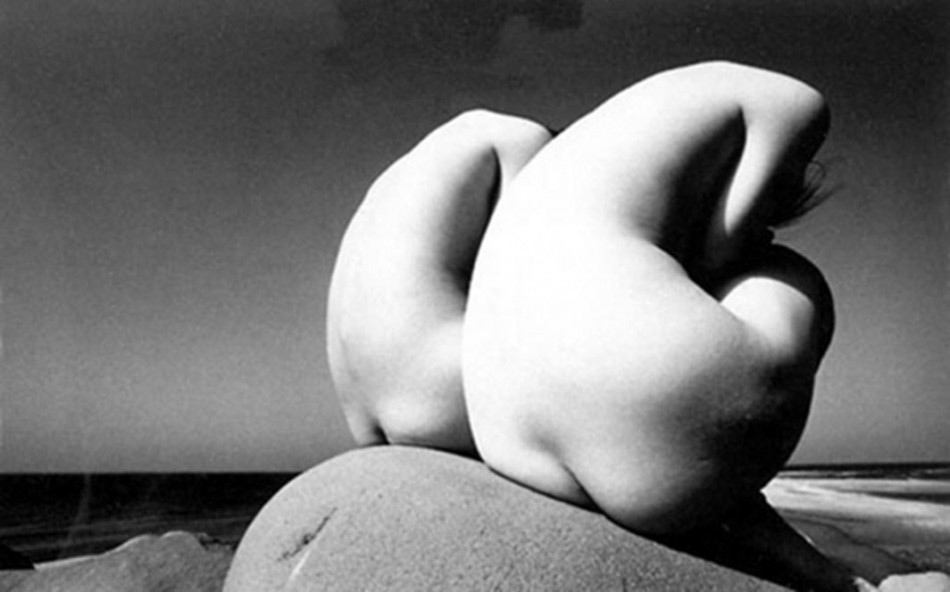

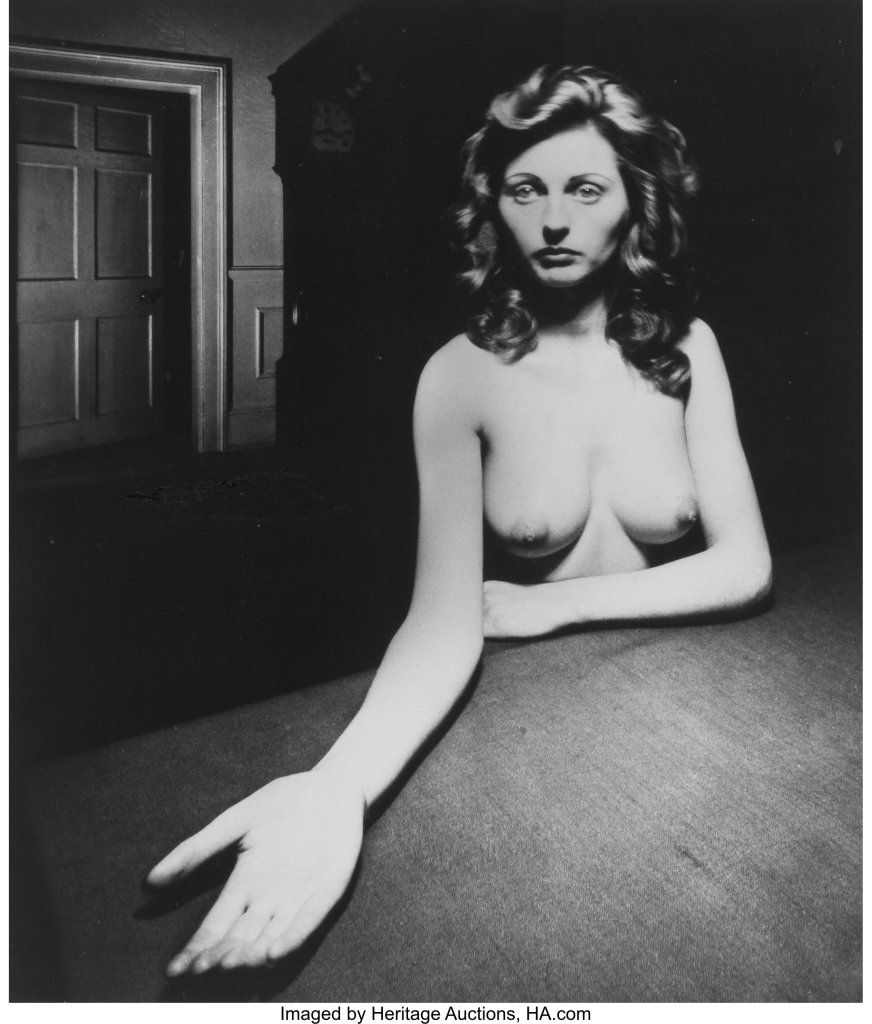

In the 1950s, when many British photographers were still limited to documentary photography or classic portraiture, Brandt took a radical turn toward aesthetic experimentation. His work with the female nude established him as one of the most innovative photographers of the century. Armed with an old Kodak camera with a wide-angle lens, he began photographing the human body in unusual ways: from extreme perspectives, with strong distortions, and in environments charged with strangeness.

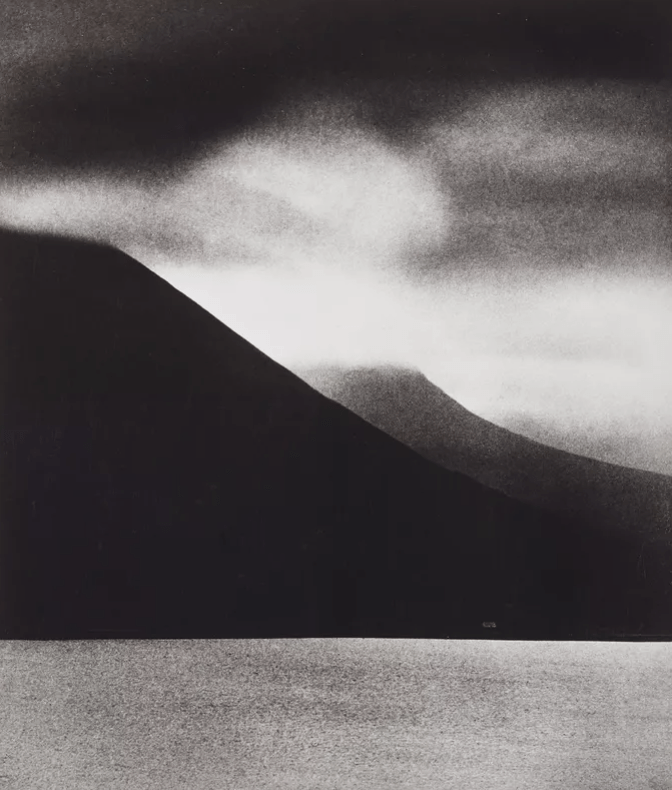

In Perspective of Nudes (1961), a key book from this period, bodies appear as almost abstract forms: elongated torsos, legs like columns, feet like mountains, breasts like dunes. Often placed in austere rooms or coastal landscapes, the bodies do not seek eroticism, but rather a sculptural resonance. These images are marked by a deliberate interplay between the sensual and the dreamlike, the physical and the metaphysical.

The use of wide-angle lenses was an aesthetic choice that completely transformed the perception of the body. The extreme closeness, combined with the unusual angle, distorted the proportions and transformed each figure into a less conventional form. The texture of the grain, the natural light entering through the windows or striking the stones by the sea, and the absence of color contribute to an atmosphere where the human figure seems suspended between the real and the unreal. His approach is considered one of the most important contributions to 20th-century nude photography, due to its formal audacity and emotional depth.

In the last decades of his life, Brandt devoted himself primarily to editing his work, preparing retrospectives, and writing about photography. Although his output declined, he continued to experiment with printing techniques, reframing, and editing his most iconic images.

In 1977, a major retrospective was held at the Hayward Gallery in London, confirming his status as the undisputed master of British photography. His work directly influenced subsequent generations of photographers, from conceptual artists to contemporary photojournalists. His approach to the body, portraiture, and shadow left a mark that still resonates in photography today.

Bill Brandt’s work is, above all, a way of looking at the world with depth, mystery, and poetry. Although he changed themes and styles throughout his life, he always maintained a very personal vision: he was not only interested in showing what was before his eyes, but also what lay behind appearances. His photographs are not simple documents: they are images that make us think, that invite us to imagine.

One of the most important aspects of his work is the use of light and shadow. Brandt understood that light not only serves to illuminate, but also to create atmospheres. His deep shadows, his stark contrasts, his dark corners speak to us of emotions, secrets, and silences. In many of his photographs, shadows occupy more space than light, creating a visual atmosphere that is sometimes unsettling, other times intimate, and always evocative.

Brandt was also a great visual storyteller. Although he rarely explained his images, each one seems to tell a story. For example, in his first book, The English at Home, he not only shows how rich or poor people live in England, but also suggests relationships, tensions, and social differences. A well-dressed family in an elegant dining room contrasts with a working-class family in a simple kitchen, but both scenes have something in common: calm, routine, everyday life viewed with respect, without obvious judgment.

His wartime work also has a special power. He photographed the people who lived through the London bombings, especially those who slept on the subway for safety. But he didn’t do so with exaggerated drama or easy compassion. He showed these people with dignity, with a humanizing perspective. They were harsh images, yes, but also full of empathy.

A key part of his work is portraits of writers and artists. Unlike other photographers, he didn’t aim for his subject to «look good.» He wanted to show them candidly. Sometimes he used the subject’s house as a background; other times he preferred very harsh, almost theatrical lighting. But there was always more to it than just a face.

Undoubtedly, one of his most original and daring works was his series of distorted nudes. He used a camera with a wide-angle lens that distorted the human body, enlarging some parts and reducing others. This made the bodies look like modern sculptures, sometimes unreal, but always suggestive. These photos were not erotic in the classical sense, but poetic, as if the body were part of the landscape. Many of these nudes were taken in bright interiors, with a window in the background or on a white bed, which created a soft and quiet atmosphere.

At first, this type of photography confused many critics. They didn’t know if they were artistic, provocative, or just plain weird. Over time, however, it became clear that Brandt was breaking the rules of how the body should be shown in photography. He wasn’t just interested in physical beauty, but in the mystery of the body, its ability to suggest emotions, shapes, and textures.

Bill Brandt’s work is profound, varied, and coherent. He went through many stages, but always maintained a very personal style. He knew how to look at the world with attention, sensitivity, and freedom. He was a documentarian, a portraitist, an experimenter, and in each of these roles, he contributed something new. He didn’t strive for technical perfection, but rather for visual and emotional impact. That’s why his photographs continue to surprise, move, and provoke thought, decades after they were taken.

Deja un comentario