Deborah Turbeville was born on July 6, 1932, in Stoneham, Massachusetts, to a wealthy family who alternated between an elegant home north of Boston and their summer home in Ogunquit, Maine. Her childhood was spent surrounded by a cultural environment that included visits to the opera, cinema, and theater, which early on strengthened her aesthetic sensibility.

At just 19, she moved to New York with acting aspirations, but was soon hired by designer Claire McCardell as a workshop assistant and in-house model, her first exposure to the fashion world. This environment led her to meet Diana Vreeland, which culminated in her first editorial job at Ladies’ Home Journal, then Harper’s Bazaar (1963–65), and later as fashion editor at Mademoiselle (1967–71).

However, the dynamics of publishing didn’t appeal to her; she was drawn to visual creation. In the 1960s he acquired his first Pentax camera and began to experiment, a training that was consolidated after a workshop in 1966 with Richard Avedon and Marvin Israel. It was then that Turbeville partially abandoned editing to dedicate himself to photography.

Deborah Turbeville’s photographic career unfolded at an unusual intersection between fashion and art, with a narrative sensibility and a distinct aesthetic that challenged the visual standards of the publishing industry for over three decades. Unlike many fashion photographers who worked within a defined commercial framework, Turbeville was able to forge an unmistakable style that escaped the logic of consumption to give way to an intimate, melancholic, and profoundly feminine visual poetic.

Working as an editor in the early 1960s for magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar and Mademoiselle, she began to understand the dynamics of the publishing world, the visual language of women’s publications, and the role that image played in the construction of femininity and desire. However, she soon felt limited by the rigidity of these structures and began to develop a deeper interest in photography as a means of expression.

During this early period, she met two key figures in her development: Richard Avedon, the master of portraiture and formal elegance, and Marvin Israel, the influential art director of Harper’s Bazaar and collaborator of photographers such as Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander. It was with them that she took an intensive photography course that would change her life. Israel, in particular, encouraged her to explore a more personal, introspective, and experimental approach.

In the mid-1970s, already with a camera in hand, Turbeville began producing works that broke the traditional molds of fashion photography. It was at this point that his true artistic career began.

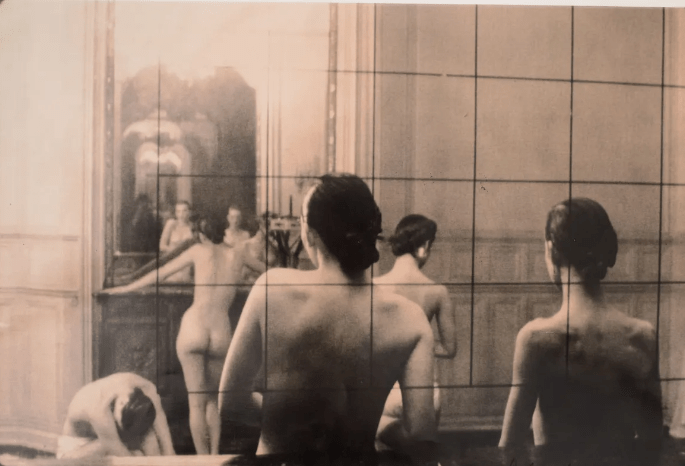

The turning point came in 1975 with the publication of the Bathhouse series in American Vogue, where he photographed five models in a ruined old Russian bath in New York. The images, far from extolling physical beauty or clothing, presented spectral female figures, dressed in muted tones, devoid of glamour, with absent gazes and seemingly fragile bodies. The worn, damp, and decaying surroundings added to the atmosphere of restlessness and nostalgia.

This work attracted attention. While some criticized her for depicting sick, passive, or vulnerable women, others, like the art critic for The New York Times, praised her for revolutionizing the visual language of fashion. With this series, Turbeville introduced the idea that fashion photography could also be a psychological narrative, an ambiguous tale, an emotional evocation. She wasn’t interested in selling clothes, but in telling a story.

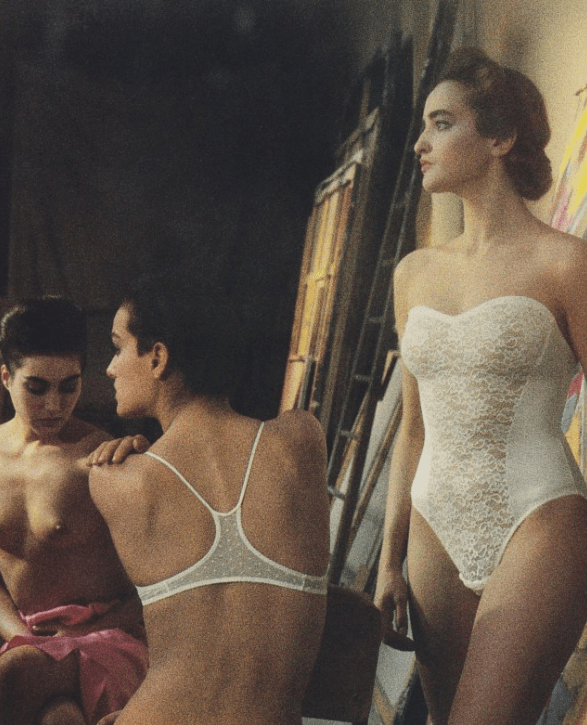

In contrast to her contemporaries such as Helmut Newton, with his aggressive eroticism, or Guy Bourdin, with his saturated color and surreal compositions, Deborah Turbeville cultivated an introspective and atmospheric visual language. Her use of muted tones, deliberate out-of-focus, evident grain, and unstructured composition distanced her from the dominant advertising aesthetic and brought her closer to a painterly, even literary, sensibility.

The physical treatment of his photographs was also an essential part of his aesthetic signature. He scratched negatives, cut and glued prints, added tape or stains, and even re-photographed previously manipulated images. This artisanal and almost obsessive gesture of destroying and reconstructing the image spoke to a deeply personal vision of the medium: for Turbeville, photography was not only a record of what was in front of the camera, but a manifestation of inner states.

Furthermore, he distanced himself from the dominant ideal of beauty. His models rarely looked at the camera, did not smile, or pose with a dominant attitude. Their bodies, often in motion or out of focus, seemed to float within atmospheres charged with silence and ambiguity. His sessions evoked a kind of existential theater where time seemed suspended.

Throughout his career, Turbeville collaborated with the world’s most influential fashion magazines, including Vogue (American, Italian, French, and Russian editions), Harper’s Bazaar, L’Uomo Vogue, The New York Times Magazine, and Mirabella. However, he never allowed himself to be absorbed by the logic of the market. He always maintained a critical distance from the fashion system and used his commissions as spaces to explore psychology, memory, nostalgia, the passage of time, and deterioration.

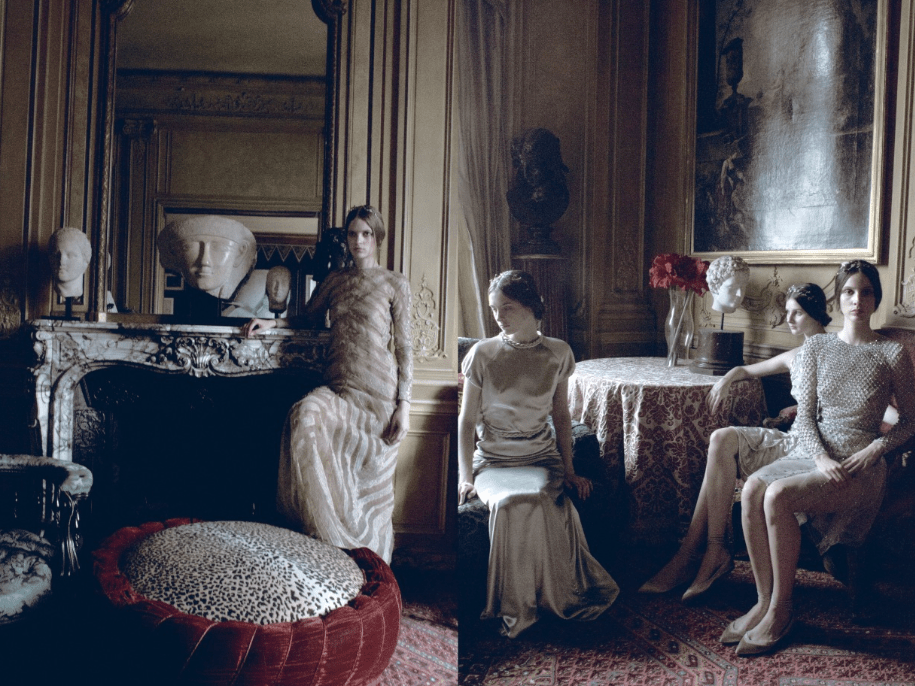

During the 1980s, she was one of the few photographers regularly commissioned by Vogue, but always asserting her own aesthetic vision. She was known for working with 35mm and medium-format analog cameras and for preferring locations that evoked abandoned spaces: crumbling mansions, empty convents, forgotten public baths, dusty palaces, and shadowy ruins.

In 1981, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, then an editor at Doubleday, commissioned her to photograph secret and forgotten places in the Palace of Versailles. The result was the book Unseen Versailles, a project that took her more than two years and ultimately cemented her place in artistic photography. Turbeville accessed sites that were not open to the public and captured a dreamlike version of the famous palace: shadowed rooms, broken angels, damp-eaten walls, torn curtains, a world of ruined beauty.

This work was not only recognized with the American Book Award, but was also exhibited in prestigious institutions such as the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Museo Tamayo in Mexico, and the Houston Museum of Art. With it, Turbeville definitively crossed the border between fashion and art.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Deborah Turbeville continued producing photographic series for fashion houses such as Comme des Garçons, Guy Laroche, Valentino, Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, and Nike, albeit always under her own aesthetic conditions. One of her most memorable collaborations was with Valentino, photographing the collections in Italian palaces and forgotten gardens that evoked scenes from Visconti’s films.

At the same time, she developed independent publishing projects in cities such as St. Petersburg, New Orleans, San Miguel de Allende, Prague, Budapest, and Newport. She was drawn to places steeped in history, the scars of time, cities where opulence had given way to neglect. These series were collected in books such as Studio St. Petersburg (1997), Casa No Name (2009) and Past Imperfect (2010).

She also took celebrity portraits, albeit with an unusually intimate approach. In 2004, for example, she photographed Julia Roberts for The New York Times Magazine in a shoot filled with shadows, floating fabrics, and reflections, moving away from the usual Hollywood glamour.

Toward the end of her career, Turbeville continued to produce personal works, but less frequently. She lived between New York and Mexico, particularly in an old mansion in San Miguel de Allende, which she restored and converted into a studio, and which served as the setting for many of her later photographs.

Deborah Turbeville’s visual universe stands as a persistent whisper among ruins, a poetic mist floating over the canon of 20th-century fashion photography. While her contemporaries celebrated the brilliance, color, and exuberance of the body, Turbeville went in the opposite direction: her camera turned toward decay, gloom, and the absent. Her work, far from the exaltation of hegemonic beauty or commercial fetishism, invokes a spectral aesthetic, a visual meditation on time, memory, and the feminine condition.

Deborah Turbeville was a photographer who viewed fashion from a completely different perspective than her colleagues. Instead of showing glamorous clothes or perfect models posing for the camera, she created mysterious, silent, and emotional scenes. Her images weren’t meant to sell, but rather to convey a feeling: that of something about to disappear, to fade away, like a memory or a dream we can’t quite grasp.

One of the most striking aspects of her work is the atmosphere. Many of her photographs seem to have been taken in abandoned places: old houses, empty public restrooms, ruined palaces, or rooms with peeling walls. These spaces aren’t just backdrops; they are a fundamental part of the image. They convey a sense of loneliness, nostalgia, and frozen time. There is no movement or forced joy. Rather, there is a calm that can seem sad, but is also very beautiful.

Her models also deviate from the norm. They don’t pose provocatively or smile, or look at the camera, as if in another world. They appear distracted, thoughtful, melancholic. They aren’t there to attract attention, but to inhabit the image with a calm, sometimes fragile presence. With this, Turbeville constructed a different image of women: not as a decorative object, but as someone with an inner life, a mystery.

Furthermore, her photographs have a very distinctive look. Unlike other fashion images that strive for sharpness, brightness, and intense colors, Turbeville’s are soft, blurry, sometimes with spots or scratches. She wanted them to look old, worn, as if they had been stored for years in a box. For her, photography shouldn’t be perfect, but rather bear the marks of the passage of time.

Turbeville used black and white with great sensitivity, and when he worked in color, he did so very subtly, with muted, warm tones. Nothing in his images is strident. Everything has an air of mystery. Sometimes it even seems like we’re watching scenes from an old film or fragments of a dream. This way of working makes his photographic series resemble personal diaries or found albums. There is something intimate and secret about them. He often combined several images on a single sheet, as if they were parts of a single idea. He also mixed photos with handwritten papers, adhesive tape, stains, or clippings. He was very interested in the photographic object, not just the image itself. His works appear handmade, as if each one were a unique piece.

Another key point in her work is the use of time. In her images, things don’t seem to be happening in a specific present. There is no current events or «current» fashion. Everything seems old, out of date. Therefore, although her photographs appeared in fashion magazines, they didn’t follow the rules of the market. Turbeville preferred to create an emotional sensation rather than show a product.

Her way of seeing the world continues to inspire many photographers and artists today. And although many of her images were commissioned by magazines or major brands, she never lost her personal style. Turbeville managed to use fashion as an excuse to talk about deeper themes, such as memory, loneliness, the passage of time, or what it means to be a woman.

Deborah Turbeville was not your average fashion photographer. She was an artist who used the camera to explore feelings, forgotten places, and new ways of looking at people. Her work invites us to pause, to look closely, and to accept that in the blurred, the old, or the broken, there is also beauty.

Books published by Deborah Turbeville

Unseen Versailles (1981)

Wallflower (1978)

Studio St. Petersburg (1997)

Past Imperfect (2010)

No Name House (2009)

Deborah Turbeville: The Fashion Pictures (2011)

Deja un comentario