Photography, since its invention in the 19th century, has been not only a means of documentation, but also an artistic language, a tool of memory, and a way of seeing and constructing the world. Today, we live in an era dominated by digital technology, where images are instantaneous, omnipresent, easily manipulated, and ephemeral. However, in this hyperconnected context, many photographers, artists, and amateurs continue to turn to analog photography not only out of nostalgia, but because they find in it something that digital photography, with all its speed and precision, cannot offer. Analog photography, with its slow pace, its imperfections, and its physical nature, offers an experience that goes beyond the final image: it is a different way of seeing, of relating to time, to materiality, and to the act of photography itself.

The first thing that analog photography offers us is a sensorial and physical experience that digital photography cannot replicate. The photographer who loads a roll of film into their camera, measures the light, carefully chooses each frame, and later dives into the darkroom to develop their negatives is engaged in a manual process, requiring time, patience, and attention. Each step of the process involves a tangible interaction with the material: the sound of the film being wound, the mechanical click of the shutter, the smell of the developing chemicals, the gradual appearance of the image in the tray under the red light. This tactile relationship with the image, with its physical medium, generates a deep emotional connection with the photograph being created. It’s not just about capturing an image, but about building it from the ground up.

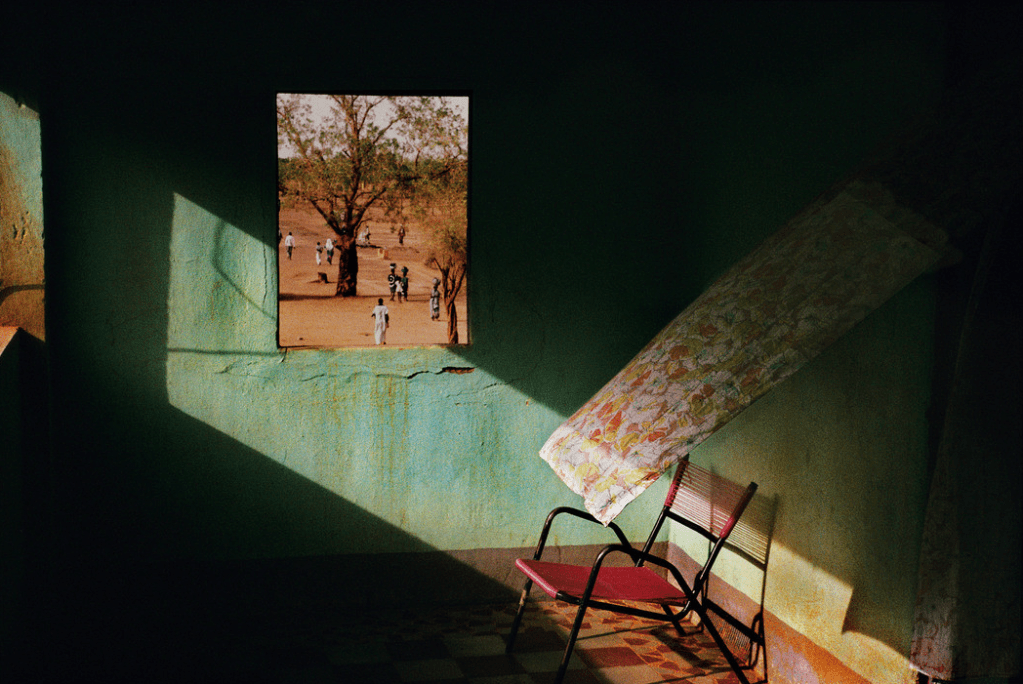

Elliott Erwitt

Furthermore, analog photography introduces a different relationship with time. In a world accustomed to immediacy, where each image can be viewed and shared in seconds, the analog process forces us to slow down, to think before shooting, to rely on memory and intuition. Not being able to see the image immediately after capturing it implies a surrender to uncertainty, a faith in the photographic act itself. It’s not about correcting on the fly, repeating the shot until it’s «perfect,» but rather accepting the result as the fruit of a conscious decision and a unique moment. That waiting, that space between the act of photographing and seeing the developed image, restores to the photographer a sense of mystery, of expectation, of a connection with the invisible.

This temporality is also reflected in the limited number of shots a roll of film offers. While a digital memory can store thousands of images, a 35mm roll has 36 exposures, and a medium-format roll has between 10 and 16. This limitation forces us to think about each image, to mentally preview it before taking it, and to be selective and careful. This economy of shooting teaches us to look with greater concentration, to not depend on chance or abundance, and to value each frame as if it were unique. Many photographers who have returned to analogue say that this restriction has improved their observational skills and visual sensitivity.

Harry Gruyaert

Another dimension where analog photography offers a unique experience is in image aesthetics. Photographic films, each with their own specific characteristics, generate images with a texture and depth that many consider impossible to replicate digitally. Film grain is not a defect, but an essential part of the analog visual language, a form of visual vibration that gives character to the image. The colors of Kodachrome, the black and white of Tri-X, the softness of a Portrait—these are elements that have defined photographic styles and continue to be revered by photographers around the world. Furthermore, analog photography tends toward a smoother reproduction of tonal transitions, resulting in a more organic, less «clinical» image than that of many digital sensors.

This aesthetic is not merely a technical matter; it entails a certain relationship with the world. Analog images often convey a sense of greater truth, of greater emotional density, precisely because they have not been digitally altered. Although darkroom editing allows for certain adjustments, such as contrast or cropping, the scope for intervention is much more limited than in digital photography. This gives analog images an aura of authenticity, of fidelity to the lived moment, which is often lost in the era of Photoshop and automatic filters. In an age where digital images can be completely fabricated, analog photography presents itself as a material testimony, as a direct imprint of the world on the photographic medium.

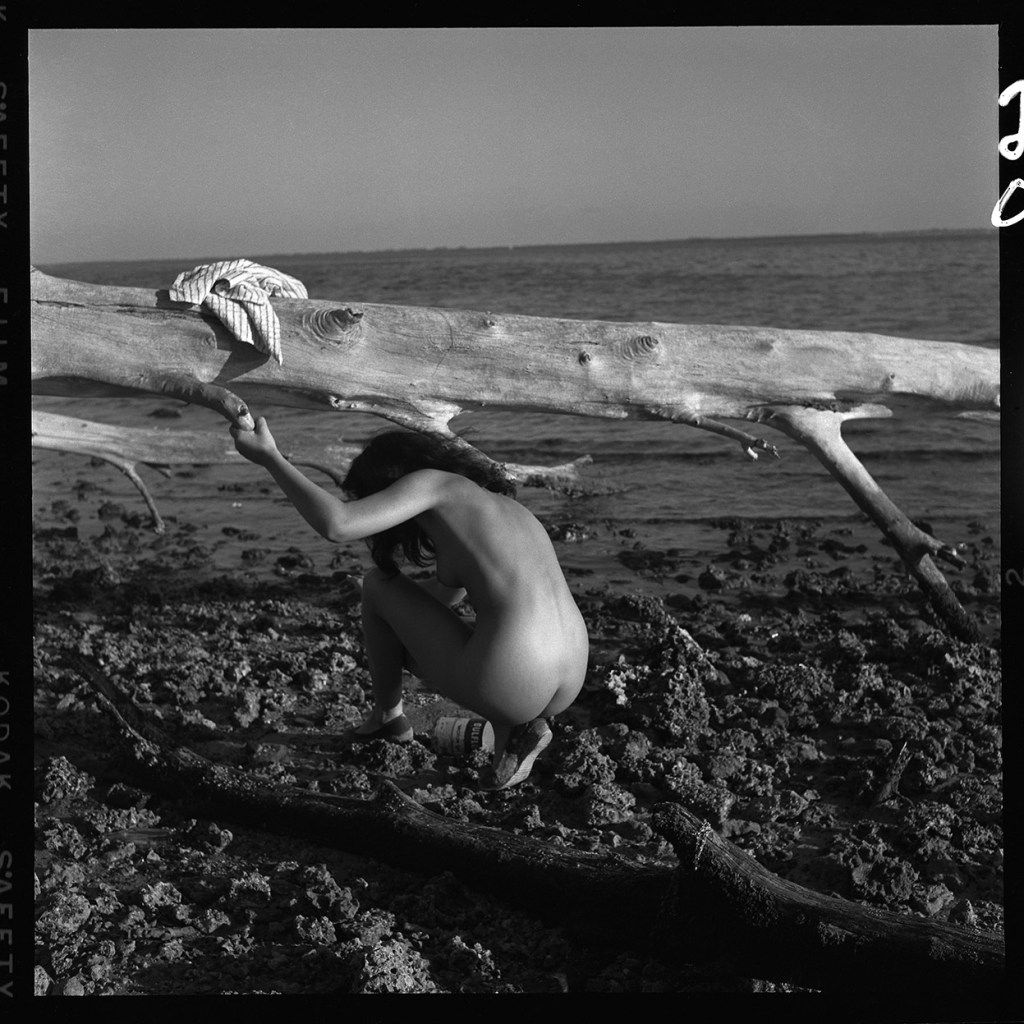

Bunny Yeager

It is also important to highlight the material value of analog photography. A negative is a physical object, a unique piece that can be archived, preserved, manipulated, and passed on as part of a personal or historical legacy. In contrast, digital files are ephemeral, dependent on constantly changing devices, formats, and operating systems. A file lost due to a hard drive failure or a cloudy day can mean the final disappearance of an image. In contrast, a properly stored negative can last for more than a century. This durability gives analog photography a dimension of permanence, of physical memory, of tangible history. Boxes of family negatives, aging albums, and printed photos with rounded edges are part of the imagination of many generations and are a testament to the power of the image as an object.

Of course, digital photography has also brought enormous benefits. Its immediacy, low cost, ease of editing, and dissemination have revolutionized the field of photography and opened it up to millions of people around the world. The ability to experiment without limits, to learn quickly, and to share images on social media has generated a global visual culture of undeniable richness. However, this same abundance can lead to saturation, a trivialization of the image. When everything can be photographed effortlessly, when every moment is recorded and shared in real time, the image loses some of its weight, its ability to move, to make us stop and look.

Garry Winogrand

In this context, analog photography represents a gesture of resistance, a way of recovering the value of time, of attention, of the image as a profound act. Photographing on film today is not a technical necessity, but an aesthetic choice. It’s a way of saying: not everything should be immediate, not everything should be perfect, not everything should be shared. There is beauty in the imperfect, in the ephemeral, in the artisanal. There is value in making mistakes, in learning from them, in waiting for the outcome. There is something profoundly human in the slowness of the process, in the surprise of what is revealed, in the materiality of the image.

Furthermore, analog photography fosters a more intimate relationship with the camera and the environment. Mechanical cameras, without screens or automation, require full attention: focusing manually, calculating exposure, understanding light. This type of photography develops skills that are often lost in digital photography, where everything is automated. But beyond the technical aspects, the act of looking through an optical viewfinder, feeling the resistance of the shutter, and advancing the film with the lever creates an almost bodily connection with the camera, which becomes an extension of the body and the eye.

Garry Winogrand

In recent years, this connection has been rediscovered by new generations who, far from rejecting digital photography, are exploring analog photography as a way to reconnect with the essential. Many young photographers combine both worlds: shooting on film, scanning negatives, editing digitally, and sharing online. This coexistence demonstrates that analog is not an anachronism, but a current alternative, an enriching complement. It’s not a war between formats, but rather a recognition of what each can offer us.

In short, analog photography teaches us to see things differently. It invites us to pause, to think, to feel, to accept that the image is not only a reflection of the world, but also a subjective construction, a process, an experience. In times of speed, of mass image consumption, of the loss of wonder, analog photography restores the possibility of contemplation, of making mistakes, of hope. It reminds us that photographing is also an act of faith: believing that light, time, and chemistry can capture a fragment of the world and transform it into memory, into art, into testimony. And that, in its apparent fragility, is one of the greatest strengths of the analog medium. It’s not about returning to the past, but rather about rediscovering a way of seeing and feeling that still has much to offer us.

Deja un comentario