Ernst Haas was born on March 2, 1921, in Vienna, Austria, into a cultured and humanist family. His father, Karl Haas, was a prominent bookseller and art collector, which led Ernst to grow up surrounded by books, paintings, and classical music. From a young age, he was exposed to a refined aesthetic sensibility, influenced by art, poetry, and philosophy. Rather than initially gravitating toward photography, Haas had aspirations of becoming a painter or a doctor. He briefly studied medicine at the University of Vienna, but his studies were interrupted by World War II.

During the war, Ernst Haas lived through difficult times. Austria was annexed by the Nazi regime in 1938, and many freedoms were curtailed. Haas was not mobilized as a soldier due to health problems, but his experience during these years profoundly shaped his outlook on the world. During this time, with no formal training as a photographer, he became interested in photography as a way to document reality and, at the same time, express a deeply personal vision.

After the war, with a borrowed Leica, he began photographing the streets of Vienna, capturing the difficult everyday life of the postwar period. One of his most significant early works was a series on Austrian prisoners of war returning from the Russian front. This report, shot in 1947 and published in Heute magazine, not only gave him widespread visibility but also demonstrated his talent for capturing emotionally charged and humane moments with carefully crafted aesthetics. From that moment on, Ernst Haas decided that photography would be his life’s work.

Ernst Haas’s professional career is a journey marked by creative independence, the continuous exploration of visual language, and a profound fidelity to his poetic vision of the world. From his early years in postwar Vienna to his international recognition as a pioneer of color photography, Haas forged a career that challenged the conventions of photojournalism and expanded the expressive possibilities of the photographic medium.

Following the success of his series on Austrian prisoners of war, published in Heute magazine in 1947, Haas was invited to join the Magnum agency in 1949. The proposal came from Robert Capa, who, impressed by the emotional impact and formal refinement of his images, considered him a necessary addition to enrich the agency’s profile. Although Ernst Haas enthusiastically accepted the invitation, his relationship with Magnum was always unique: while he actively collaborated with the agency, he also defended its aesthetic independence. From the outset, he made it clear that he was not a war photographer or a political chronicler. His interest lay in capturing life in its simplest and most profound manifestations: movement, light, mood.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Haas began traveling extensively, both in Europe and America. It was during these years that he began his transition from black and white to color, using Kodachrome film, which allowed him to faithfully and richly capture the light and color nuances of his surroundings. While many photographers were still wary of color, associating it with commercialism or superficiality, Haas saw a different dimension in it. This vision distinguished him and made him a pioneer.

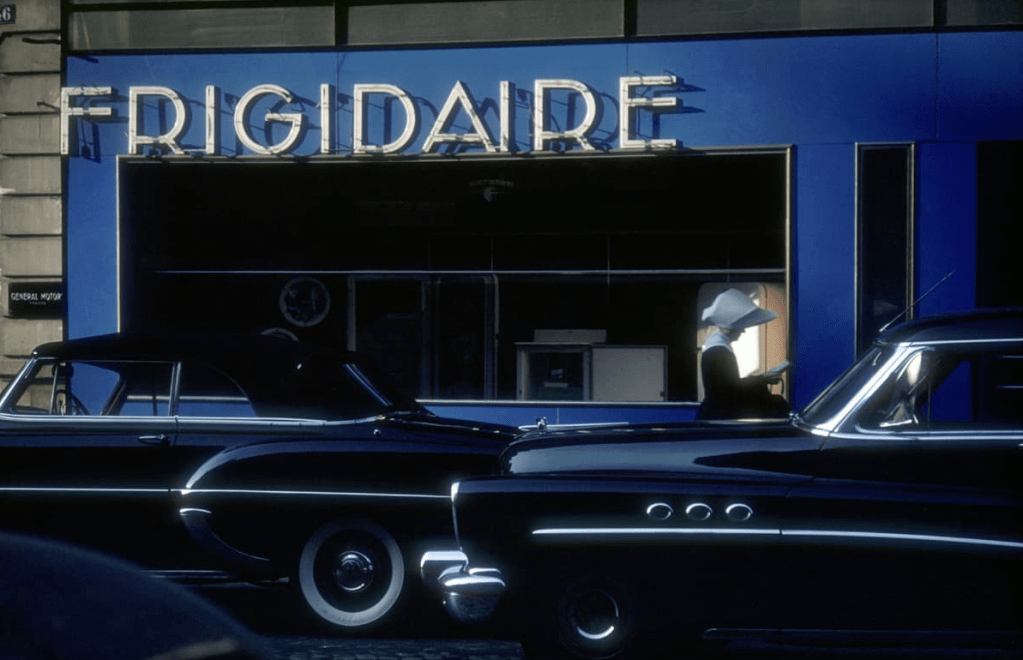

In 1953, Life magazine (the most influential photography publication at the time) dedicated a special issue to his series, Impressions of New York. It was the first time the magazine had dedicated an entire issue to a single photographer’s full-color portfolio. This publication was a turning point not only in his career but in the history of photography. The series depicted a New York unlike that documented by other photographers: neither heroic nor miserable, but magical. Moving cars transformed into chromatic blurs, neon lights reflected in puddles, buildings seen through curtains or steamed-up windows: Haas offered an impressionistic vision that challenged the logic of the «decisive moment» that predominated in the documentary canon.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Haas was one of the most active and renowned photographers in the world. He completed numerous assignments for magazines such as Life, Look, Holiday, and Vogue, and traveled to dozens of countries: Japan, Burma, India, Egypt, Brazil, Mexico, Morocco, Spain, Italy, France, among others. But unlike photographers who sought to portray cultural differences, Haas had a unifying vision: he sought, more than the particularities of a place, the universal resonances of the human experience. Thus, his work on religious processions in Spain or the streets of Bangkok were not ethnographic reports, but visual explorations of light, color, rhythm, and the sensation of time in motion.

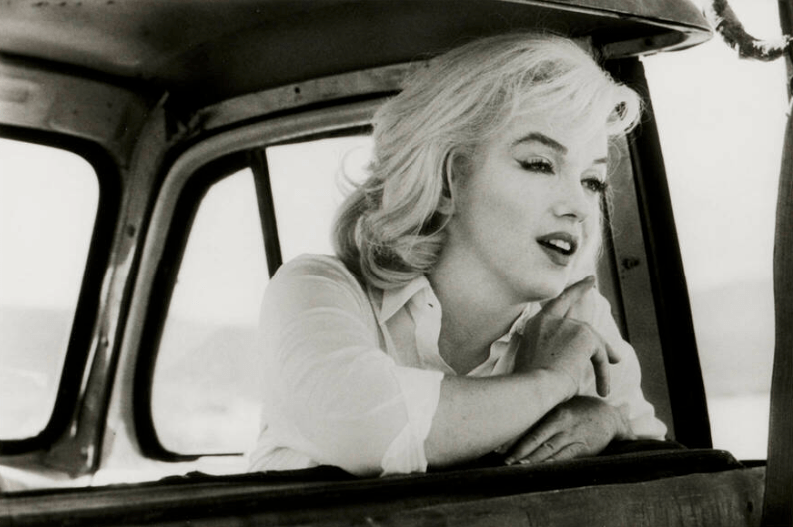

A lesser-known but equally important part of his career was his work in the world of cinema. Beginning in the 1960s, Haas collaborated as a photographer on the set of several Hollywood films, but his most emblematic work in this field is his coverage of the filming of The Misfits (1961), directed by John Huston and starring Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable, and Montgomery Clift. Haas photographed not only the filming scenes but also the intimate moments behind the scenes, capturing the emotional tension and fragility of the actors. The resulting images are profoundly human, far from the artificial glamour of commercial cinema. In them, Marilyn Monroe appears tired, vulnerable, and serene; Clark Gable displays gestures of tenderness and loneliness. This work, later published under the title On Set, was recognized as one of the best photographic coverages of cinema from the inside.

In 1962, Haas was elected president of Magnum Photos. His appointment was a sign of respect and admiration from his colleagues, although it also challenged his uninstitutional nature. During his presidency, he promoted the agency’s opening toward more experimental and subjective photography, moving away from the strict investigative reporting that had characterized the founding generation. Thanks to his influence, Magnum incorporated new styles and opened up a space for artistic photography.

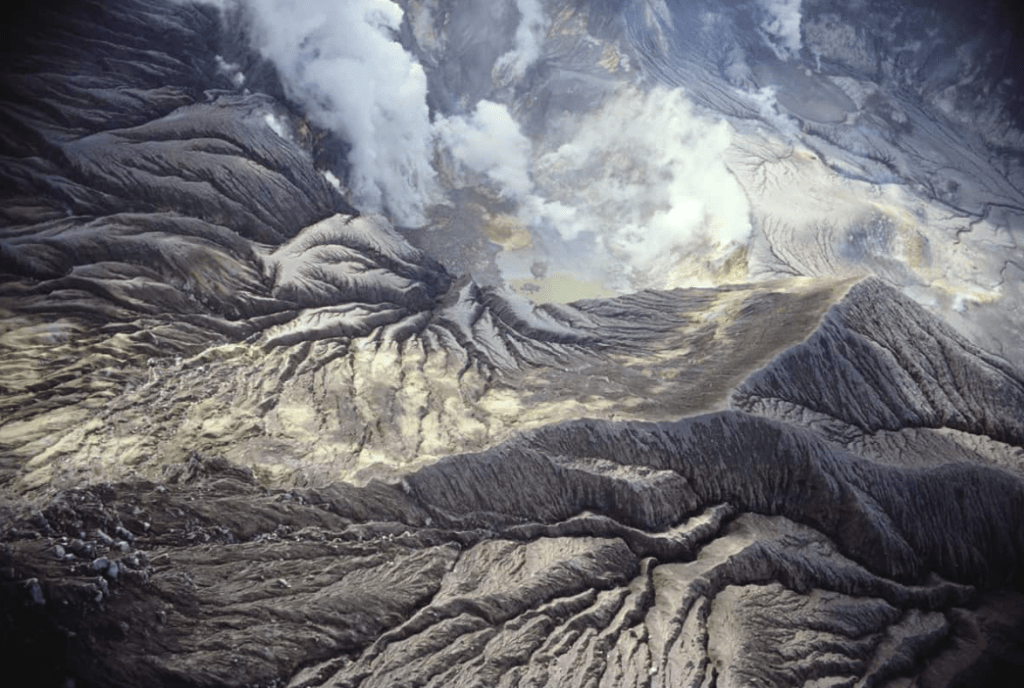

By the 1970s, Haas scaled back his publishing collaborations to focus on personal projects. It was then that he conceived his most ambitious book: The Creation (1971), a visual exploration of the elements of nature, inspired by the biblical text of Genesis. Far from being a religious book, The Creation is a contemplative work, a hymn to the harmony of the natural world. Photographs of deserts, clouds, waves, glaciers, and volcanoes intertwine in a visual sequence that evokes both Romantic painting and Eastern poetry.

Throughout his career, Haas was invited to exhibit at major museums and galleries, and his images were included in landmark shows such as The Family of Man (1955), curated by Edward Steichen at MoMA, which celebrated the unity of human experience through photography. But the true institutional recognition of his work came in 1971, when MoMA itself organized a solo exhibition devoted exclusively to his color work (something unusual at the time). This exhibition helped consolidate the artistic legitimacy of color in photography, a field that until then had been seen as a gray area between advertising and fashion.

In the 1980s, already considered a master, he continued to work intensively. He taught workshops, wrote thoughtful texts on photography as an art of perception, and continued to photograph with an increasingly free and abstract gaze. His interest in forms, reflections, and light became more refined, closer to the language of modern painting. At the same time, he mentored new generations of photographers, who found in him an alternative to classic documentary narrative.

Ernst Haas died unexpectedly on September 12, 1986, in New York, at the age of 65. His death left a void in the world of photography, but his legacy continued to grow. Over time, his figure has been revalued not only as an innovative color technician, but as a visual poet who transformed photography into an emotional, sensorial, and philosophical experience.

Ernst Haas’s work is one of the most unique and revolutionary of the 20th century, due to the profound transformation it proposed within the photographic language. Haas was neither a chronicler of great wars nor an activist of social protest. His work focused on the invisible: on what happens between one moment and another, on silence, on flux.

One of the most notable characteristics of his evolution was the transition from black and white to color, and the way this shift led him to develop a completely different aesthetic. While many of his contemporaries (including Magnum colleagues such as Henri Cartier-Bresson) clung to black and white as a symbol of seriousness and photographic «purity,» Haas embraced color as an opportunity to break the limits of documentary realism. Instead of using color as mere decoration, he turned it into an expressive tool.

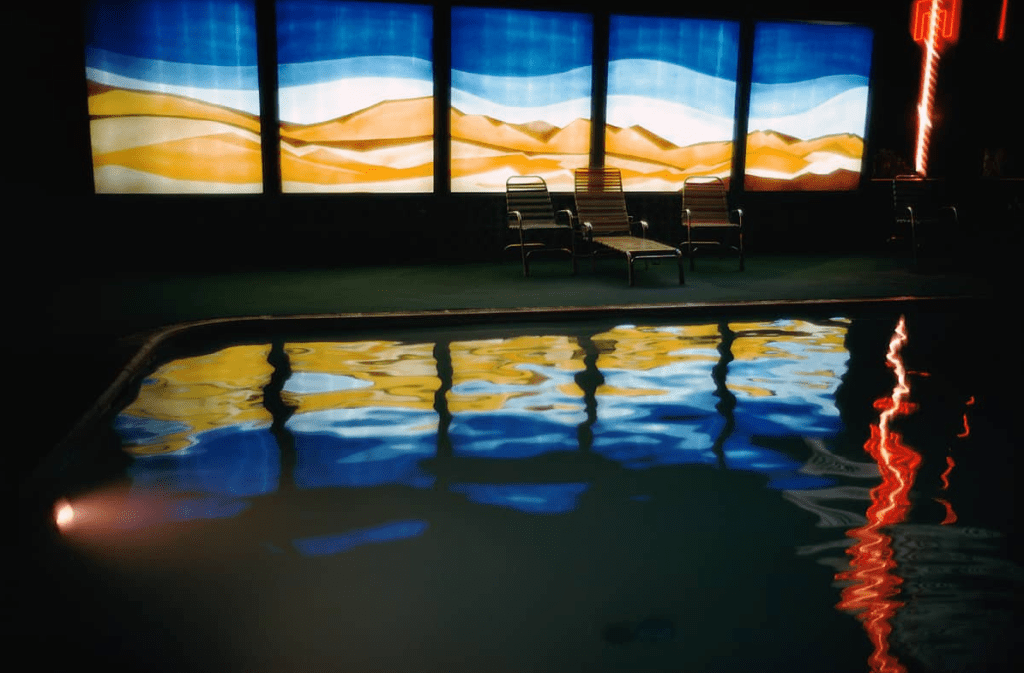

His best-known color photographs—cars moving through New York, lights reflected in puddles, crowds blurred in an almost painterly flow—do not simply seek to report on a place or a moment. They focus on capturing atmospheres, fleeting emotions, visual harmonies that exist for an instant and then disappear. Rather than constructing linear narratives, Haas creates abstract compositions, often without a clear subject, where the essential element is the relationship between light, form, texture, and color.

A recurring resource in his work is movement. Unlike the photographic tradition that associates sharpness with truth and objectivity, Haas challenges that convention. The blurred image in his work doesn’t signify error, but rather freedom: the freedom to represent movement, to show how the world looks when we perceive it with emotion rather than precision. In his celebrated Motion series, he experiments with slow shutter speeds, panning, and overexposure, achieving images that resemble abstract paintings. As he himself wrote: «The true visual journey is not that which freezes the world, but that which lets it vibrate.»

In series such as Impressions of New York (1953) (published in Life), Haas transforms the world’s most photographed city into a dreamlike place, made of neon lights, smoke, rain, and flashes. Instead of a harsh New York, full of straight lines and hurrying crowds, Haas shows a living city. These images marked a break with the dominant paradigm of mid-20th-century photojournalism and anticipated many of the visual explorations later undertaken by photographers such as Saul Leiter, Joel Meyerowitz, and William Eggleston.

A key point in understanding his work is its relationship with time. Unlike the classical approach that conceives of photography as a tool to «stop» the decisive moment (as Cartier-Bresson proposed), Haas sees photography as a way of revealing the flow of time. In this sense, he connects more with cinema, and even more so with philosophical notions of time as duration, constant change, becoming. Hence his interest in movement, in unfinished gestures, in images that are not fixed, but seem to advance.

His way of seeing the world was profoundly lyrical, but also universal. He never sought to impose a vision, but rather to share a slower, more open way of seeing. In an interview, he said: “I don’t seek to capture what I see. I seek to capture what I feel when I see.” That statement encapsulates the essence of his photography: a sensorial, emotional, silent search. An art that doesn’t shout, but leaves a profound mark.

Ernst Haas’s legacy is not measured solely by his photographic work, but also by the influence he has had on generations of visual artists. His commitment to color as a legitimate medium paved the way for many contemporary photographers. Today, when color is the dominant language in photography, it’s hard to remember how radical his choice was in the 1950s.

Furthermore, Haas knew how to combine aesthetic sensibility with technical rigor. Despite his intuitive language, his images reveal a precise understanding of light, composition, and the handling of photographic equipment. He was a master of the Leica, but also worked with SLR cameras and experimented with multiple color films, such as Kodachrome, which allowed him to achieve vibrant tones and soft contrasts.

Finally, his ethical vision of the world is evident in the way he approached his subjects. He was never invasive, never exploited suffering, or sought easy drama. His gaze was empathetic, even when photographing from a distance. Haas understood that photography should be an act of respect, a way of honoring life.

In 1962, he was appointed president of Magnum Photos, confirming his influence within one of the most influential agencies in the history of photography. His leadership helped Magnum expand its reach to new forms of visual storytelling and experimentation with color.

In 1971, MoMA in New York organized a solo exhibition dedicated exclusively to his color work, entitled Ernst Haas: Color Photography. It was one of the first exhibitions of color photography at such an institution, marking a milestone in the acceptance of color as a legitimate artistic medium.

In 1986, shortly before his death, he received the Hasselblad Award, one of the most prestigious in the world of photography, in recognition of his innovative contribution to photography. He also received posthumous tributes, such as the major retrospective organized by the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York in 1989.

Published Books

Haas’s work has been compiled in several books, many of which are essential for understanding the evolution of 20th-century photography. Among the most important are:

- The Creation (1971): His most famous book, a visual celebration of the natural world, inspired by the biblical text of Genesis. With images of volcanoes, clouds, seas, and forests, it is a visual manifesto that unites photography, poetry, and spirituality.

- In America (1975): A visual chronicle of the American landscape and urban life, from New York to the Southwest, capturing the essence of the country with a lyrical approach.

- Ernst Haas: Color Correction (2011): Published posthumously by Steidl and curated by William A. Ewing, this book revealed a new selection of his color work, with images that had never been published before. It represented a critical reexamination that reaffirmed him as a pioneer in modern photography.

- Ernst Haas: New York in Color, 1952–1962 (2020): An intimate exploration of his New York decade, where he perfected his visual language. This book shows Haas in full freedom of expression, portraying taxis, traffic lights, windows, and crowds, all bathed in the chromaticism of his sensibility.

- Ernst Haas: On Set (2015): brings together his images taken on Hollywood sets, especially of The Misfits, showcasing his talent for capturing the intimate atmosphere of cinema.

We also recommend visiting the official Ernst Haas Estate website: http://www.ernst-haas.com where you can find information curated by his family and archives.

Deja un comentario