The photographer’s gaze is not formed in a vacuum. It is not a simple technical exercise or an innate talent that springs forth like a miracle, isolated from human experience. The gaze is cultivated, forged, and nourished by multiple activities. Behind every image lies a story not only of the moment captured, but also of the eye that observes, of the body that moves to frame, of the finger that presses the shutter, of the soul that interprets and transforms the visible world. In that intimate and silent gesture of the photographer who raises the camera and decides when and how to freeze a portion of time, an entire universe of experiences, knowledge, memories, intuitions, wounds, pleasures, and obsessions is concentrated. The photographic gaze is, ultimately, a mirror that reveals the photographer’s interior. What truly nourishes that gaze is not only light, but everything that precedes it: personal experiences, cultural influences, artistic yearnings, aesthetic references, the reading of the environment, historical conditions, technical decisions, emotional impulses. All of this and more blends in a unique way that turns photography into an extension of the self.

Each photographer constructs their gaze from a different place. Some come to photography as a way to escape reality; others, on the contrary, seek to capture it with obsessive fidelity. Some see it as an art form, others as a document, others as a form of resistance. However, all of them, without exception, share one common element: the need to see. Not just to look, but to see deeply. That ability to see what others don’t perceive or to give value to the everyday and seemingly banal. The camera becomes a tool to intensify that gaze, to structure it, to share it. But the root of everything lies in the eyes and the sensitivity of the person holding it. A photographer can spend hours walking through a city without taking a single image, simply observing, absorbing the secret language of things, refining their perception. In that active waiting, in that attentive contemplation, their gaze is nourished.

Ian Berry

Life experience is one of the fundamental pillars of this visual formation. A photographer who has experienced pain, war, loss, exile, or marginalization inevitably bears these marks on their vision of the world. But so does anyone who has known beauty, wonder, love, childhood, or the contemplation of nature. The gaze thus becomes a cartography of what has been experienced. The images taken by someone raised in the countryside are not the same as those of someone who grew up in a big city; someone who has traveled extensively observes with restless, open, comparative eyes; someone who has witnessed a social injustice may seek to capture it to denounce it. This autobiographical dimension is intertwined with the collective: the photographer’s personal history inevitably intersects with the history of their country, their generation, their era. In many cases, the impulse to photograph is born from an urgent need to bear witness, to preserve a moment that would disappear without the mediation of the camera. In others, it is about exploring the invisible, the emotional, the symbolic.

Culture, in its broadest sense, also shapes the gaze. Photographing from a Western tradition is not the same as photographing from an Indigenous, African, or Asian perspective. Each culture has its own particular relationship with the image, with representation, with time, and with the body. Visual education, whether formal or informal, also plays a role. Those who have grown up surrounded by painting, film, literature, architecture, or music develop a more complex visual sensibility. Photography, although a visual art, interacts with all other arts. Many photographers were first painters, writers, architects, or musicians, and they have brought those influences, those ways of composing, of structuring space, of suggesting emotion, to photography.

Martine Franck

Technique, far from being an obstacle to expression, can be a privileged channel for refining one’s vision. Knowing how to manage light, master exposure, understand framing, and play with depth of field or blur allows the photographer to translate their inner vision into a precise image. It’s not about technical virtuosity, but about coherence between what one feels, what one wants to say, and how one achieves it visually. Sometimes, a blurry image can say much more than a perfectly focused one, if it responds to a poetic or narrative intention. Technique, therefore, is a means, not an end. The same goes for equipment: a large-format camera, a DSLR, a cell phone, or a pinhole camera offer different ways of seeing and recording. Some photographers prefer to limit themselves to a single type of camera or lens to force an aesthetic and sharpen their perception. Others explore multiple devices to expand their expressive range. In any case, the equipment doesn’t determine the gaze, but it can shape it, condition it, and lead it down certain paths. The use of editing, digital or chemical development, is also part of that language: it’s not what you see, but how you translate it visually.

Inspiration, although sometimes presented as a magical flash, is also cultivated. An attentive photographer is constantly inspired: by a book, a conversation, a film, a song, a face, a shadow, a memory. The gaze is fueled by curiosity, by the capacity for wonder, by the willingness to be affected by the world. Many photographers keep notebooks where they jot down ideas, fragments of dialogue, drawings of future compositions, and visual references. The creative process is longer and more invisible than it seems. Behind a great photograph, there can be weeks, months, or even years of preparation, research, and mistakes. The photographer also needs time not to photograph, to look without a camera, to empty themselves and refill themselves. In those moments of pause, the deepest growth often occurs. The eye needs to rest, but also to see differently. It needs doubt, crisis, distance.

Sarah Moon

There’s an emotional and narrative dimension that often unconsciously guides the camera. A photographer may be drawn to certain colors, shapes, and lights, without knowing exactly why. The camera then becomes a way to explore these inner impulses, to discover intimate truths. In that sense, photography is also an act of self-discovery. Over the years, many photographers discover that they repeat certain themes, gestures, and atmospheres. These patterns aren’t whimsical: they reflect deep obsessions and personal quests.

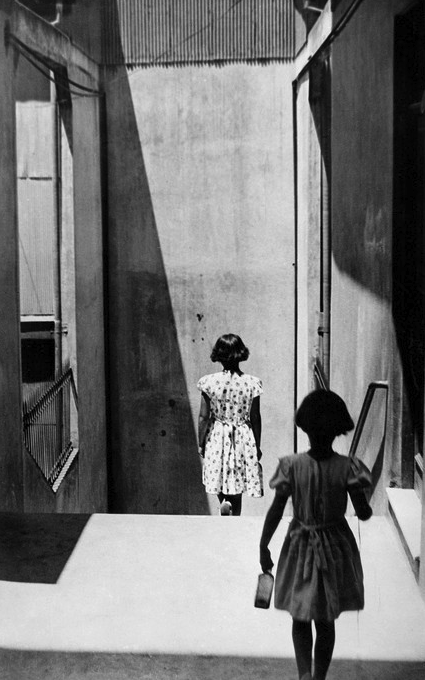

All of this manifests itself differently in each photographer. In the work of Sebastião Salgado, for example, one perceives a gaze that seeks human dignity amidst suffering, marked by a humanist sensibility and a background in economics that allows him to understand social structures. In Sergio Larraín, his gaze is poetic, introspective, charged with silence and depth. His work seems to seek the invisible within the visible, the spiritual in the everyday. Larraín immersed himself in cities with a keen eye, but also with a soul searching for meaning. Geometry, shadows, girls crossing paths on the stairs, the moment when the world seems to stop—all of these nourished his vision. His shift away from photography in his later years was part of the same impulse: a deeper, more interior search. In Daido Moriyama, the gaze dissolves into urban fragmentation, into the grainy, the chaotic, the fleeting. The city is a visual torrent that the Japanese photographer translates into stark contrasts, abrupt framing, and violent shadows. Moriyama draws his gaze from the street, from aimless walking, from the visual noise of modern Tokyo. For Josef Koudelka, the nomadic, wandering gaze constructs landscapes of exile and desolation, with an aesthetic that blends the documentary with the poetic. Each of them, and so many others, has drawn their gaze from a different place, but all have managed to construct a recognizable, coherent visual language, intimately linked to their being.

Sebastiao Salgado

Sergio Larrain

It’s sometimes thought that the photographic gaze is reduced to a matter of talent or style, but in reality, it’s the result of a long, profound process. It’s nourished by what one has lived, what one has learned, what one has felt. It’s nourished by doubts as much as certainties. It changes over time. A photographer’s gaze doesn’t look the same at twenty as it does at fifty. The gaze matures, refines, becomes more complex or more essential. Some become more minimalist or more abstract; others move from color to black and white, or vice versa. Some retreat into intimacy, others broaden their field of vision. The evolution of the gaze is also the evolution of being.

Ultimately, what truly nourishes a photographer’s gaze is life itself: everything they touch, observe, hear, dream. The gaze is not only made up of what they see, but also of what they imagine, what they fear, what they desire. That’s why each photograph is unique, because it is the result of an unrepeatable gaze. Photographing isn’t just recording reality; it’s transforming it, reinterpreting it, revealing it. The photographer’s gaze isn’t a simple mechanical eye: it’s a sensitive filter, an active memory, a silent voice that speaks in images. And like any voice, it needs constant nourishment. Seeing demands total dedication, an openness to the world and to oneself. That’s why photography, when it’s authentic, when it’s born from a living gaze, remains one of the most powerful and moving forms of human communication.

Josef Koudelka

Deja un comentario