Lillian Bassman was born on June 15, 1917, in Brooklyn, New York, the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants. From an early age, she became interested in art, an unconventional path for women of her time. She grew up in a liberal and bohemian environment, which prompted her to seek intellectual and creative independence. She studied at the prestigious High School of Music and Art in Manhattan, where she began to explore the possibilities of drawing and painting. Later, she attended the Art Students League and later the WPA Federal Art Project, which furthered her artistic training.

In the mid-1930s, she met Paul Himmel, a photographer also trained as an artist, whom she married in 1935. Her relationship with Himmel was both personal and professional: he was a constant support during times when Bassman doubted her place in the art world.

Although her early life was tied to painting, her discovery of photography came in the 1940s, when she began working as an art assistant at Harper’s Bazaar magazine. It was the publication’s art director, Alexey Brodovitch, who encouraged her to take a more active role in photography. Brodovitch, like her of Russian origin, was a key figure in the magazine’s aesthetic renewal and became one of her greatest mentors.

Lillian Bassman developed one of the most unique careers in fashion photography. Not only for the originality of her vision, but also because she broke with the visual conventions imposed by the editorial market within the most influential magazines. Her career, which spanned the 1940s to the beginning of the 21st century, can be divided into three major stages: her rise and consolidation as a fashion photographer at Harper’s Bazaar, her voluntary retirement from the publishing world, and her rediscovery and artistic comeback decades later.

Bassman began her photography career within a very unique creative ecosystem: Harper’s Bazaar magazine, artistically directed by Alexey Brodovitch, which also featured photographers such as Richard Avedon and Louise Dahl-Wolfe. Bassman began as a graphic designer and art director for the Junior Bazaar supplement, aimed at a youth audience. It was in this context that her editorial vision was formed: she had a clear mastery of visual rhythm, layout, and typography, which she would later translate to her photography.

Her transition to photography was organic. Brodovitch encouraged her to pick up a camera when he noticed her strong aesthetic sense and sensitivity to images. In 1947, she began publishing her own photographs, and her images soon became distinctive for their painterly and experimental nature.

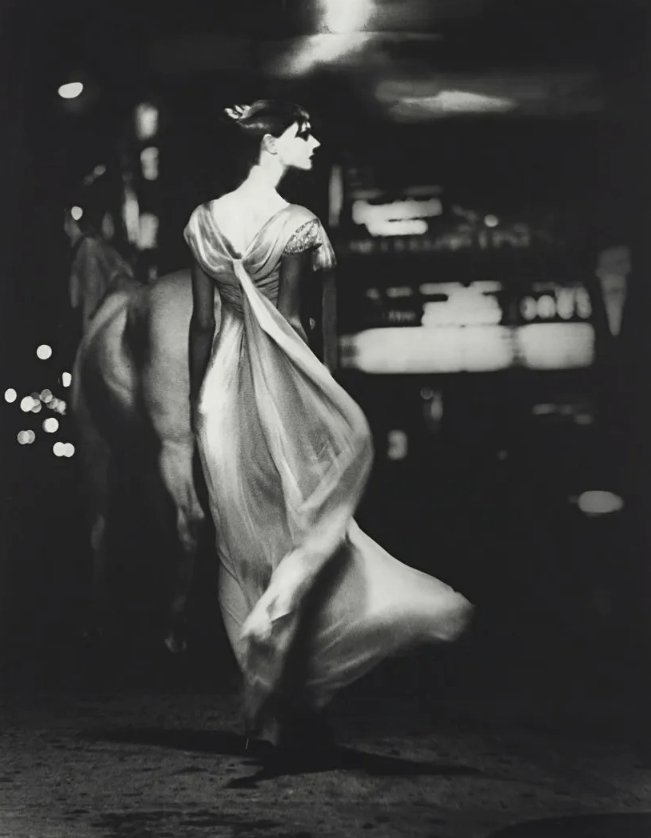

In this early period, Bassman began to define a visual language centered on chiaroscuro, dramatic out-of-focus effects, unexpected framing, and the emotional interaction between model and environment. His work was characterized by a highly personal use of black and white, a play with tonal values that gave his images a dreamlike and sensual quality.

Unlike his contemporaries, Bassman did not seek an objective representation of clothing, but rather to convey atmosphere. He often photographed models at angled angles, against the light, or in motion, exploring silhouette, texture, and transience. These choices reflected his interest in subjectivity and visual emotion. Some of his most iconic images were published in the centerfolds of Harper’s Bazaar, such as lingerie shoots or almost abstract portraits of women looking through a curtain or with their faces barely visible.

Over the years, she collaborated closely with renowned designers such as Christian Dior, Balenciaga, and Chanel, who saw his style as a way to elevate their creations beyond the mere fashion catalog. Rather than simply displaying clothes, Bassman integrated them into a self-contained aesthetic world.

During this period, she was also a pioneer in giving space to African-American models or models with atypical physiques, something very uncommon in editorial fashion at the time. Her commitment to individuality and non-standardized beauty set her apart from many of her colleagues.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the fashion industry began to undergo radical change. The rawer, more realistic documentary style promoted by magazines like Vogue and by new photographers like Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin was beginning to replace the romantic, painterly aesthetic that Bassman cultivated.

Tired of the limitations of the publishing world and the new demands of the market, Bassman made a radical decision: she moved away from commercial photography, abandoned commissions, and literally destroyed many of her negatives, archives, and working prints. This action, which she herself described as «necessary,» was both a symbolic break and an emotional catharsis.

For nearly two decades, Bassman pursued other activities: she taught design and photography at institutions like Parsons School of Design, conducted visual experiments for herself, and largely stayed away from the media. This period is still poorly documented, but it is known that she did not completely abandon art; she simply ceased her involvement in publishing.

In the 1990s, Lillian Bassman experienced a surprising resurgence. At over 70 years old, and thanks to the interest of young photographers, curators, and editors, her work was rediscovered and revalued. Encouraged by this rediscovery, Bassman began revisiting her archive and producing new works from old materials. Most notably, she did this using digital tools, such as Photoshop, which allowed her to continue manipulating images in an artisanal way but with new technologies. This digital shift was not a step backward, but a natural extension of her style: it allowed her to expand her range of effects, playing with transparencies, layers, contrasts, and textures with even greater freedom.

During this period, she produced portraits of contemporary women, special editorials, and revisited her classic work. Her exhibition at the International Center of Photography in 1996 marked her official return to the art scene, and she has since participated in exhibitions in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Unlike other artists who simply recycle their work, Bassman used this second phase to reinvent herself. The new images weren’t simple restorations: they were refined, different versions that explored themes such as the body, time, sensuality, and death in greater depth. She also experimented with self-portraits and body movement studies, demonstrating a creative vitality exceptional for her age.

This period brought her the recognition that had been denied her for decades. She was celebrated as a pioneer, a visionary of female photography, and as a bridge between classical modernism and the digital age. She unwittingly became an inspiration for new generations of visual artists, especially women who were seeking a different way of representing the body and fashion.

Lillian Bassman was not simply a fashion photographer. Her work transcends the editorial realm to occupy an intermediate zone between photography, painting, and visual poetry. Her oeuvre, built over several decades, represents a meditation on femininity, form, light, and gesture. More than documenting dresses or trends, Bassman sought to create atmospheres where women could express themselves with an intimate, sensual, and free voice.

Her legacy can be approached from multiple perspectives: aesthetics, technique, gender discourse, artistic subjectivity, and the evolution of the photographic medium. In all of these, Bassman was an innovator. Bassman’s work is marked by a strong sense of suggestion. Unlike other fashion photographers of her time, Bassman favored an introspective aesthetic. Her models don’t shout, they don’t pose for the viewer; they seem to be in an inner world, sometimes absorbed, other times in subtle movement, as if they were characters in a choreography.

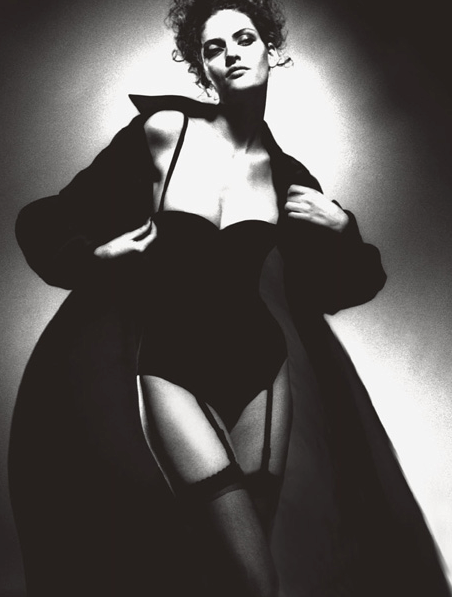

This choice is not fortuitous. Bassman believed that photography should suggest more than it shows, that mystery is a form of beauty. That’s why many of his images are shrouded in shadow, blurred at the edges, or shot through with glazes and highlights that blur parts of the face or body.

In this sense, Bassman is an indirect heir to pictorial symbolism, graphic modernism, and also expressionist cinema. Chiaroscuro, the use of black and white, and diagonal composition are tools she uses not only to embellish, but to charge the image with poetic tension. Fashion, in her view, is not a product, but a visual language of subtle emotions.

One of the most fascinating aspects of her practice was her work in the darkroom. There, Bassman broke with the idea of photography as a document. She manipulated negatives obsessively, using all kinds of artisanal techniques to alter the original image. In many cases, she cut out fragments of the negative, combined them with others, or reprinted them at different densities.

This form of manual intervention in photography was very uncommon at the time, especially in the commercial context of fashion magazines. Rather than seeking clarity or fidelity to reality, Bassman produced painterly, atmospheric, almost unreal images.

His laboratory functioned like a modern painter’s studio. There he destroyed, erased, and reconstructed. The resulting photographs moved away from documentary recording and approached abstract painting, printmaking, and even oriental calligraphy with their elegant, diffuse strokes. Sometimes, in his images, a hand blends into the background, a face becomes a blur, or a dress seems to dissolve in the light. These «imperfections» were deliberate, constructed from an aesthetic sensibility that prioritized the emotional over the descriptive.

Later, with the advent of digital technology, Bassman adopted tools such as scanning negatives and editing in Photoshop not as a technical solution, but as a new palette of artistic possibilities. This gesture speaks to his experimental spirit and his commitment to the evolution of his visual language.

The representation of the female body is perhaps one of the most complex themes of her work. In her images, women are neither passive objects nor sexualized symbols. They are introspective subjects, sometimes absorbed, sometimes in motion, but always self-possessed. Their gestures are delicate, ambiguous, often melancholic or sensual, but never vulgar. In place of the dominant male gaze, Bassman proposed a feminine and feminist gaze before the term was common in artistic discourse.

Her models appear almost immaterial, as if they belonged to an emotional rather than a physical plane. There is a subtle eroticism in her images, but it is an eroticism based on sensitivity, not exploitation. Sensuality is constructed through the veil, the fold, the minimal gesture.

This way of representing the feminine had a great influence on later photographers such as Sarah Moon, Deborah Turbeville and Ellen von Unwerth, who took up this idea of woman as a poetic, introspective and emotional subject.

Another central aspect of Bassman’s work is her treatment of time. Her images seem suspended in an indefinite temporal dimension: they are not snapshots that freeze the present, but rather memories, impressions, traces of something that has already passed.

She achieves this effect through blurring, the use of white on white, the absence of spatial context, and the manipulation of contrast. In many of her photographs, there is no clear background or recognizable location; they are rather ambiguous spaces.

Unlike other fashion photographers who sought to capture the «here and now» of a trend, Bassman presents us with an image of dilated, melancholic time. Her women are not situated in a precise historical moment, but in a timeless limbo. This is why her work ages so well: it is not tied to a decade or a passing aesthetic.

This timelessness also connects with the minimalist and modernist movements of the 20th century, where the essential, the clean, and the suggestive prevail over the narrative or the decorative.

Lillian Bassman’s influence has become increasingly evident over time. In recent decades, her aesthetic has been embraced by fashion editorials, luxury brands, photographers, and contemporary visual artists. Her approach to the body, light, and mystery has been cited as inspiration by photographers such as Peter Lindbergh, Paolo Roversi, and Sarah Moon.

Beyond her aesthetic influence, her work raises important questions: Can commercial photography be art? What does it mean to look from a feminine sensibility? How can we express the mystery of the body without falling into the obvious?

In an era where fashion photography was defined by technique and objectivity, she championed intuition, error as beauty, and gesture as narrative. Her elegant, incomplete gaze not only redefined the role of women in the image but also paved an artistic path for conceiving photography as an autonomous, lyrical, and deeply human art form.

Deja un comentario