Inge Morath was born on May 27, 1923, in Graz, an Austrian city near the Alps. She spent much of her childhood in Darmstadt, Germany, and other Central European cities. Her parents, scientists dedicated to research and teaching, belonged to an educated and cosmopolitan class. This upbringing allowed her to be exposed from a very young age to literature, music, art, and languages, elements that would profoundly influence her artistic sensibility.

In her youth, Morath experienced firsthand the radical changes of the interwar period and the rise of Nazism. These experiences, although traumatic, helped to forge a critical and committed worldview. In 1937, while still a teenager, she visited the famous «degenerate» art exhibition organized by the Nazi regime to discredit avant-garde artists. Rather than being repelled, she was deeply impressed by the works of artists such as Paul Klee, Kandinsky, and Picasso. That exhibition, paradoxically, awakened in him an aesthetic vocation and an intellectual resistance that he would never abandon.

During World War II, she studied literature, art history, and Romance languages at the universities of Berlin and Vienna. Although her background was not initially visual, she developed a deep understanding of narrative and symbolic processes, key elements that she would later apply to her photographic work. Her fluency with languages (she spoke German, French, English, Spanish, Romanian, and later learned Russian) allowed her to establish deep connections across different cultural contexts.

During the war, she was drafted to work in a German factory as part of the Nazi war effort. This experience of forced and traumatic uprooting left an indelible mark on her. As she later confessed, it was during these war years that she became convinced that, if she survived, she would dedicate her life to promoting intercultural understanding.

After the end of the war, Morath settled in Vienna, where she began working as a translator and journalist. There she met photographer Ernst Haas, who at the time was developing his career as a photojournalist for Heute magazine, a publication created by the Allies to counter Nazi propaganda. Morath wrote texts that accompanied Haas’s images, and it was precisely this collaboration that sparked her interest in photography as an autonomous means of expression. She was fascinated by the way an image could convey emotions and narratives without the need for words.

Convinced that photography could be as powerful a tool as writing, she began to teach herself. She bought a Leica, the classic camera of photojournalism, and began experimenting with urban scenes, portraits, and short visual essays. Her first works were simple, but they already showed a special attention to gesture, atmosphere, and details that revealed something profound about the people or places photographed.

In 1951, she moved to Paris, the epicenter of postwar visual culture, with the intention of entering the professional world of photography. There, she joined the Magnum Photos agency as a researcher, translator, and editor. Thanks to her command of the language and her general knowledge, she soon became a highly valued collaborator with figures such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa. In this environment, surrounded by some of the greatest names in documentary photography, Morath finally found her ultimate calling: to be a photographer.

Inge Morath’s career as a photographer officially began in the early 1950s, although her sensitivity and intellectual preparation had been developing long before. Her arrival at Magnum Photos in 1953 marked the beginning of a remarkable career, characterized by an exploration of the world from an intimate, empathetic, and deeply human perspective. At a time when photojournalism was primarily associated with action, conflict, and hard news, Morath worked with a perspective of contemplation, silent portraiture, and the poetic discovery of everyday life.

She first joined Magnum as an editor and researcher: she wrote photo captions, translated reports, and helped coordinate stories. This work brought her into contact with the most influential photographers of the time, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, who soon became her mentor. It was he who encouraged her to pick up a camera and go freelance. In 1955, after several successful reports and displays of artistic maturity, she was accepted as a full member of Magnum, becoming one of the first women to achieve this at an agency dominated almost exclusively by men.

From her earliest photographic series, Morath gravitated toward social, cultural, and anthropological themes rather than urgent reportage. Her first major series, «War on Sadness» (1955), documents life in Franco’s Spain with a perspective far removed from exoticism and direct denunciation. Through rural scenes, religious processions, solitary figures, and women covered in blankets, she constructed a visual chronicle full of ambiguity and symbolism, in which sadness is both an emotion and a collective state. This reportage set the tone for her career: she did not seek to explain, but to show and suggest.

In the following years, Morath developed a prolific activity as a traveling photographer. She produced reports in Iran, Russia, China, Mexico, the United States, Romania, Yugoslavia, Egypt, and other countries. In all of them, she maintained a constant ethic: not to impose her vision, but to learn from the context. Unlike other Western photographers, her camera projected neither judgment nor distance. On the contrary, he approached local life with respect and discretion. His command of languages was key to gaining the trust of his subjects and interpreting cultural subtleties. His work lacks a colonial or documentary-like attitude in the strictest sense; rather, it seeks resonance between the foreign and the intimate.

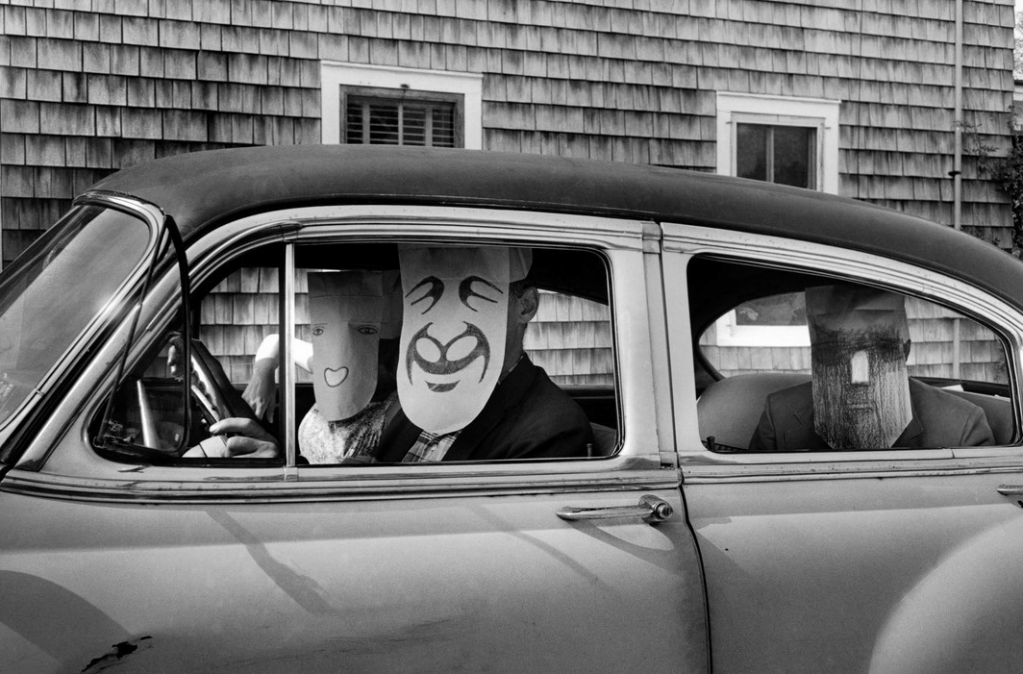

One of the most well-known moments of her career was her work on the set of the film «The Misfits» (1960), directed by John Huston and starring Marilyn Monroe. Morath was sent by Magnum to cover the shoot. Rather than limiting herself to capturing promotional images, she created a visual essay that captured the emotional fragility of the actors and the melancholic atmosphere surrounding the production. During this experience, she met writer Arthur Miller, then Marilyn Monroe’s husband, whom she later married in 1962. The marriage did not interrupt her work, but rather opened new intellectual and collaborative doors.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Morath combined personal work with editorial collaborations and exhibitions. She also produced long-term projects, such as her immersion in village life on the Austria-Hungary border, or her exploration of ethnic minorities in China. Her work evolved toward a more essayistic form, less subject to the timeliness of the press. In fact, her photography resisted the accelerated pace of modern photojournalism. She herself claimed that her greatest pleasure was observing patiently and listening with her camera.

Throughout her career, she was also interested in the relationship between image and word. She collaborated with writers such as Miller, Günter Grass, and Alberto Moravia, creating books in which text and photography dialogue equally. This fusion of languages reflects her intellectual and literary training, and her desire for photography not only to show the world, but to reflect on it.

Morath worked actively until the end of her life. In her later years, she dedicated time to organizing her archive and supporting young photographers. Her death in 2002 did not mark a definitive closure, but rather the opening of a legacy that lives on in the Inge Morath Award, presented by Magnum to emerging women photographers.

Although Inge Morath was not a media figure in the traditional sense, her work was highly respected and valued by both her peers and prestigious cultural institutions. Throughout her career, she received significant recognition that attests to the quality and depth of her work. Her discreet approach, her humanistic outlook, and her pioneering contribution as one of the first women in elite photojournalism were widely recognized, especially in the final decades of her life and posthumously.

One of the most important milestones in her career was her acceptance as a full member of Magnum Photos in 1955. At a time when professional photojournalism was almost exclusively dominated by men, joining and establishing herself at this agency founded by legends such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, and George Rodgers was an act of both breakthrough and validation. Although not a formal award, it represents one of the highest symbolic recognitions a female photographer could receive in that historical context.

Throughout her life, her work was selected and exhibited in prestigious galleries and museums around the world, including the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and museums in Vienna, Berlin, Paris, Beijing, and Moscow.

In 2000, two years before her death, the City of Vienna awarded her the Vienna Culture Prize (Wiener Kulturpreis), an Austrian recognition of outstanding figures in the arts, for their contributions to visual culture and understanding between peoples. This award was especially meaningful for Morath, who throughout her career maintained a deep connection to her home country, despite having developed much of her work abroad.

Another of the most notable recognitions is the one that bears her name: the Inge Morath Award, established in 2002 by the Magnum agency in collaboration with the Inge Morath Foundation (founded by her family and colleagues after her death). This annual award is given to female photographers under the age of 30 who demonstrate a committed and creative documentary approach, in keeping with Morath’s legacy. Through this award, her influence lives on in new generations of photographers, many of whom have become leading figures on the contemporary scene.

In addition to institutional awards, Morath was internationally recognized by critics, editors, and curators, who considered her one of the great visual storytellers of the 20th century. Her inclusion in key anthologies of photography history, such as Beaumont Newhall’s The History of Photography and Magnum Stories, edited by Chris Boot, cemented her position in the global photographic canon.

Although she never sought fame or stardom, Morath built a solid and deeply influential career, earning the respect of both the artistic and documentary worlds. Her awards were few in number, but they were significant in quality: each one reflected her integrity, talent, and unique way of looking at the world.

Inge Morath’s work can be understood as a constant inquiry into the human condition, carried out through a subtle, patient, and empathetic lens. One of the fundamental pillars of her style is the ethics of the gaze. Inge Morath did not photograph people to expose them or prove anything. His work reveals a profound respect for the subjects he portrays, whether artists, farmers, workers, children, or public figures. In his portraits, there is never a sense of artifice or forced staging; rather, it seems as if time has stopped precisely at the moment when the subject reveals himself as he truly is.

The photographer also developed an aesthetic of closeness, both emotional and physical. Her compositions tend to avoid the distance of a telephoto lens or the voyeurism of stolen instantaneousness. On the contrary, her images convey the sensation of having been constructed from within, from dialogue, from coexistence.

Formally, her photographs are characterized by an elegant visual economy, a great sensitivity to light, and precise composition. Although the majority of her work was in black and white, Morath also explored color in her later years, always with the same visual restraint. She never sought the dramatic: she preferred silences, pauses, and small signs that reveal the essential. Thus, a half-open window, a shadow on the floor, or a restrained expression can speak as much as a major event.

Another distinctive feature of her work is the way it combines intellectual curiosity and aesthetic sensibility. Thanks to her literary training and her command of several languages, Morath approached her photographic projects as cultural essays. His series on Iran, for example, doesn’t limit itself to depicting the exotic: it seeks connections between history, spirituality, and everyday life. The same is true of his travels to China, where he photographed not only major cities but also anonymous faces, rituals, and marginalized spaces. Each photograph seems the fruit of a longer conversation, an exploration that goes beyond the frame.

Inge Morath was also a pioneer in female photography, although she never used her status as a flag or a claim. She was so simply by existing, by working freely in a profession where women were relegated to secondary tasks. Her gaze provides a unique perspective: more focused on the subjective than the newsworthy, more interested in connections than in events. And perhaps that is why her legacy resonates so strongly today, as new generations of photographers seek ethical and aesthetic references outside the traditional canon.

Ultimately, the value of Inge Morath’s work lies not in its spectacularity or technical innovation, but in its coherence, depth, and humanity. In a visual world saturated by immediacy, her images invite us to look again, to pause, to listen. They remind us that photographing can also be an act of care, humility, and love for the diversity of human experience.

Recommended bibliography on this great photographer

Inge Morath: Life as a Photographer – Inge Morath Foundation / Magnum Photos, 2003.

(Visual and biographical compilation with essays by colleagues and family, published shortly after her death.)

Inge Morath: Portraits, edited by John P. Jacob – Prestel Verlag, 1999.

(Book featuring many of her most important portraits, with context about her methods and relationships with her subjects.)

Inge Morath: Iran – Steidl, 2009.

(Includes her personal photos and texts from her trip to Iran in 1956. Very useful for understanding her cultural approach.)

Magnum Stories, edited by Chris Boot – Phaidon, 2004.

(Contains a section dedicated to Morath, with her own voice and testimonies from other Magnum photographers.)

Magnum: Fifty Years at the Front Line of History, Russell Miller – Grove Press, 1999.

(Book (Historical account of Magnum Photos, including Morath’s role at the agency and how she was received in a predominantly male environment.)

Deja un comentario