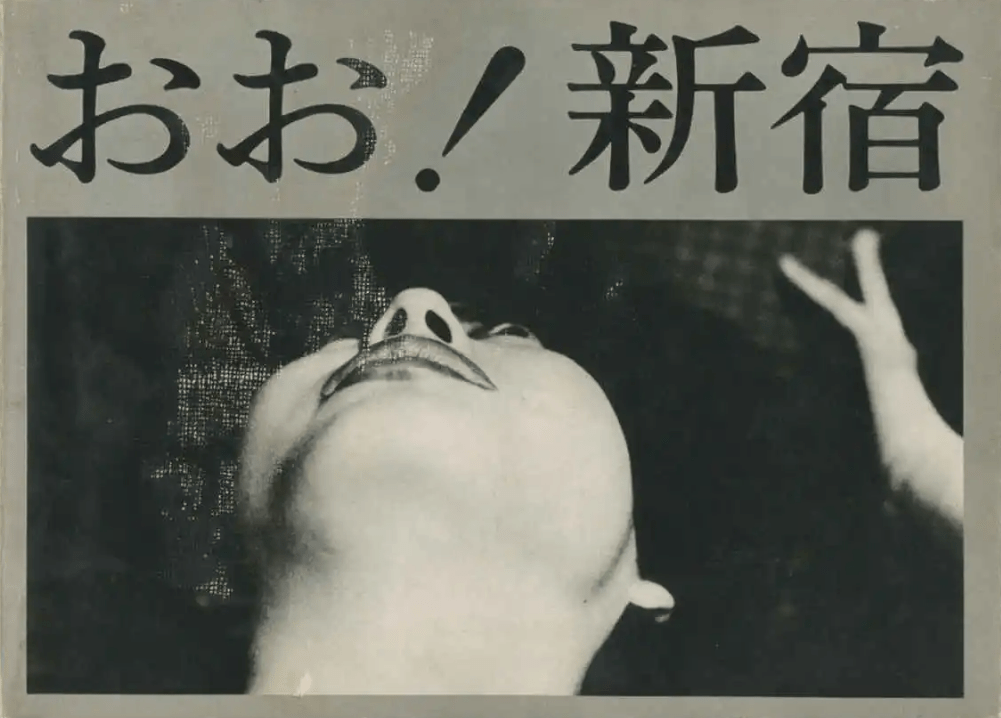

Provoke magazine was an avant-garde Japanese photography publication that, despite its brief existence, left an indelible mark on the history of art and photography. Between 1968 and 1969, only three issues were published, plus a compilation volume in 1970, underscoring its ephemeral yet intense nature. It was conceived and executed by a group of radical photographers and writers who set out to challenge the established conventions of documentary photography and boldly explore new forms of visual expression.

Provoke’s emergence occurred in a turbulent Japan, marked by profound social and political unrest, with waves of student protests, intense labor conflicts, and a palpable atmosphere of questioning the prevailing system. In this context, traditional photography, dominated by a humanist and documentary style influenced by the postwar period, was perceived by these artists as insufficient and incapable of capturing the complex and fragmented contemporary reality. This dissatisfaction generated the need for a new form of expression that Provoke sought to fill, not only documenting, but provoking and reflecting on the nature of the image in a constantly changing world.

The collective that gave birth to Provoke was comprised of key figures: Takuma Nakahira, Kōji Taki, Yutaka Takanashi, Takahiko Okada, and Daidō Moriyama. These founders united under a shared vision of discontent with the photographic status quo, feeling that Japanese photography of their time had stagnated in a conventional and often superficial representation of reality. Their goal was to dismantle pre-established narrative and aesthetic structures, seeking a rawer authenticity and a more visceral expression.

The philosophy behind the name «Provoke» was multifaceted. Not only did it seek to provoke a visceral reaction in the viewer, prompting them to question their own perceptions and the nature of the images they consumed, but it also aimed to bring about a fundamental shift in the perception and practice of photography itself. The magazine was a visual and textual manifesto, a bold statement against the sharpness, classical composition, and assumed objectivity that characterized dominant postwar photography.

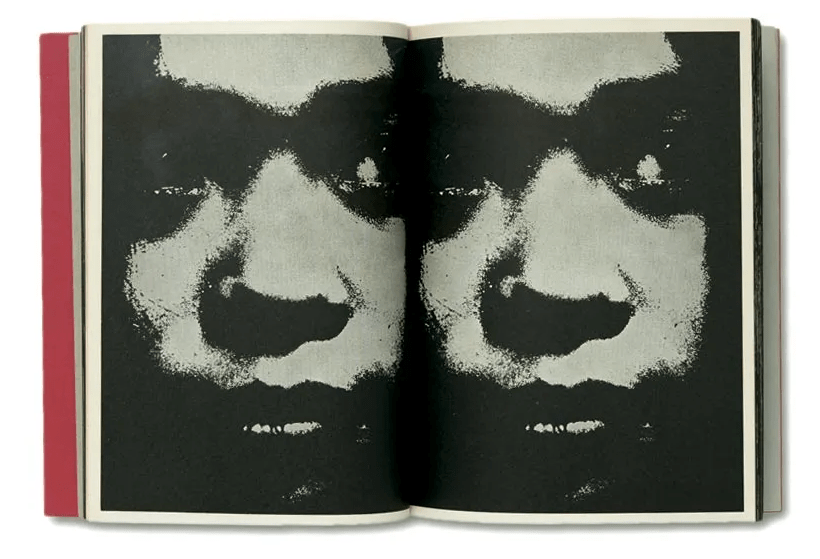

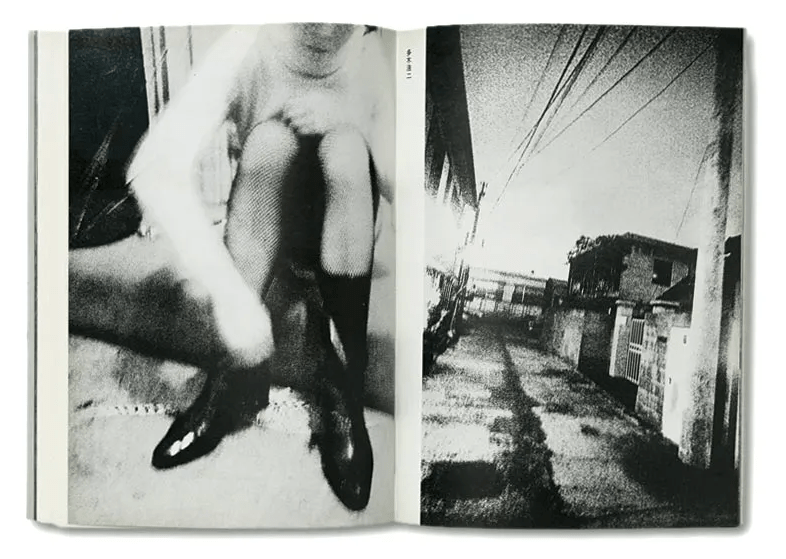

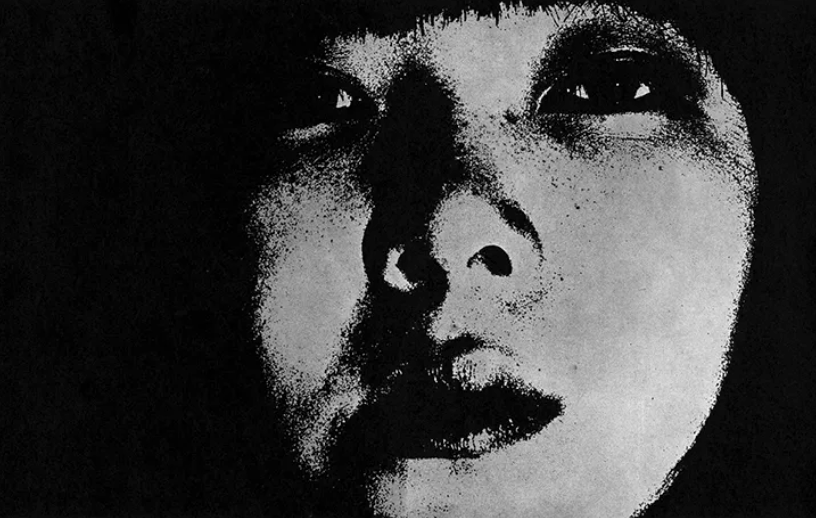

The heart of Provoke’s aesthetic lay in what would become known as «Are, Bure, Bokeh,» roughly translated as «Rough, Blurry, Out of Focus.» This triad defined an intentionally raw photography style, far from the technical neatness valued until then. Provoke’s images were characterized by excessive grain, high contrast, and an often chaotic and out-of-focus composition. This experimental approach radically opposed classical composition and the pursuit of sharpness, prioritizing instead a representation that reflected the photographer’s subjectivity and the inherent uncertainty of the era. The deliberate choice of an imperfect aesthetic was a statement: reality was neither sharp nor tidy, and photography should reflect that complexity and disorder. By privileging these qualities, Provoke transformed photography from a mere means of documentation into a powerful tool for subjective expression and critical reflection, inviting the viewer to actively participate in the interpretation of the image.

In addition to its revolutionary visual aesthetic, Provoke distinguished itself by the integration of philosophical and political texts in each issue. These texts were not simply explanatory accompaniments to the images, but integral elements that delved into the questioning of the relationship between images and language. Provoke’s founders believed that photography alone could not capture the totality of experience, and that language was necessary to explore the underlying ideas and emotions evoked by images. This combination sought a more complete and challenging experience for the reader, inviting deep reflection on the nature of representation, communication, and the construction of reality in an increasingly media-driven society. The essays explored themes such as authorship, interpretation, the relationship between the real and the perceived, and the role of the photographer in creating meaning. This symbiosis between image and text transformed Provoke into an intellectual platform that went beyond the purely visual, seeking critical dialogue with its audience.

Provoke’s style and philosophy did not emerge in a vacuum; They were the result of a melting pot of influences, both from earlier Japanese photography and Western movements, as well as from other artistic and philosophical fields. These inspirations allowed them to construct an aesthetic and narrative that, while radical, were firmly rooted in a deep understanding of the history of the medium.

Within Japanese photography, Provoke established a critical dialogue with its predecessors:

Shōmei Tōmatsu: His work on postwar Japan and the American presence, as seen in his influential series Chewing Gum and Chocolate (1959), was fundamental to the critical vision of Nakahira and Moriyama. Tōmatsu not only documented the scars of war but also explored the cultural hybridization that accompanied Japan’s modernization. His focus on subjectivity and the rawness of reality was a direct precedent for Provoke’s aesthetic, inspiring its members to seek a more honest and unadorned representation.

Eikoh Hosoe: Known for his expressionist style and his collaborations with writers like Yukio Mishima on works such as Ordeal by Roses (1961), Hosoe was a key figure. His dramatic use of extreme contrasts, deep shadows, and intentional blurring resonated significantly with the aesthetic Provoke sought to develop. Hosoe’s ability to evoke intense emotions and dense atmospheres through purely visual means demonstrated to Provoke members the power of formal manipulation to convey an emotional and subjective truth, beyond mere documentation.

Ken Domon: Although his documentary realism contrasted with Provoke’s approach, his emphasis on capturing «truth» in the postwar period was an essential point of reference. Domon represented the pinnacle of the humanistic and objective tradition in Japan. Provoke, in rejecting this objectivity, did so in full awareness of Domon’s rigor. His work served as the backdrop against which the magazine articulated its own radical departure, learning from the seriousness of his commitment to truth, yet seeking a new way of expressing it, one that embraced fragmentation and uncertainty.

Western photography also played a crucial role in shaping Provoke’s imagery:

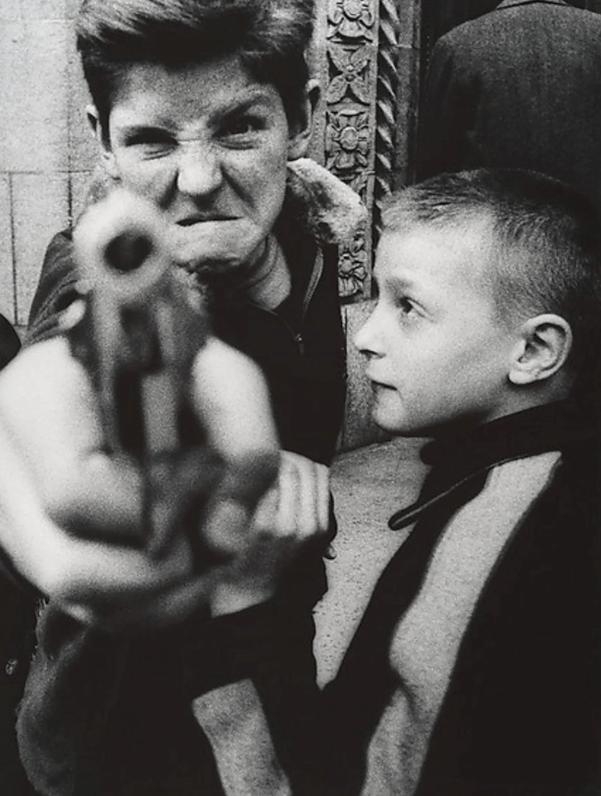

William Klein: His iconic book Life is Good & Good for You in New York (1956) showcased an aggressive and chaotic approach to street photography, characterized by haphazard framing, high contrast, and frenetic energy. Klein’s boldness in subverting compositional rules and embracing urban chaos was a direct inspiration for Provoke’s aesthetic, especially for Daidō Moriyama, who admired his ability to capture the essence of the city without tidiness or idealization.

Robert Frank: The Americans (1958) redefined documentary photography with its subjective, fragmented style. Frank was not striving for journalistic objectivity, but rather a personal and poetic exploration of the American social landscape. His melancholic approach, his often off-center framings, resonated deeply with members of Provoke, especially Moriyama, who adopted and expanded this unconventional approach to reflect Japanese urban life. Frank demonstrated that an image could be both deeply personal and a sharp social commentary.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Although to a lesser extent and in a more subtle way, the work of Mexican photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo inspired the exploration of the everyday with a poetic approach. His ability to find mystery and beauty in seemingly mundane scenes, and his use of light and shadow to create atmospheres charged with meaning, resonated with Provoke’s sensibility to elevate the ordinary to the extraordinary, albeit through a rawer aesthetic.

Beyond photography, Provoke drew from diverse intellectual and artistic currents. Its members were deeply involved with experimental cinema, seeking new forms of visual narrative and the deconstruction of images. The structuralist and existentialist philosophies of the time also influenced their thinking, particularly their questioning of reality and subjectivity. The political unrest of the 1960s, with its protest movements and radical critique of power structures, served as both the backdrop and ideological engine for Provoke. These heterogeneous references converged to help redefine photography not only as a means of recording, but as an autonomous and deeply subjective language, capable of expressing the complexity and fragmentation of human experience in a tumultuous historical moment.

Provoke’s enduring importance lies in the fundamental way they redefined photography, transforming it from a primarily documentary medium to a subjective and experimental language. This redefinition represented a radical break with the established documentary traditions that had dominated the photographic landscape until then. Provoke’s impact was immediate and profound, transforming not only Japanese photography but also resonating globally.

Before the advent of Provoke, Japanese photography was largely dominated by documentary realism and postwar humanism. This style focused on clear storytelling, balanced composition, and apparent objectivity, seeking to depict a comprehensible and often uplifting reality. Provoke categorically rejected this approach in favor of highly subjective, fragmented, and chaotic images.

The harsh, blurred, and out-of-focus approach, known as «Are, Bure, Bokeh,» became an unmistakable visual signature of the magazine and, subsequently, a defining influence for generations of photographers. This style wasn’t simply a technique; it was a philosophical statement. It vividly captured the sense of overwhelming speed of urban life in the 1960s. By embracing this aesthetic, Provoke boldly challenged the long-held idea that photography should be inherently sharp, clear, and objective. They demonstrated that ambiguity and imperfection could be powerful tools for expressing a deeper, more nuanced truth—a truth that resided in subjective experience and fragmented perception. Blurring wasn’t a technical error, but a way of communicating the transience of perception and the difficulty of capturing a constantly changing reality.

Provoke’s influence extended far beyond its short editorial life. Photographers such as Daidō Moriyama, one of its founders, continued to develop and expand Provoke’s aesthetic and philosophy throughout their prolific careers, becoming key figures in contemporary photography both in Japan and internationally. Moriyama’s work, with its distinctive grainy style, unbalanced compositions, and exploration of Tokyo’s streets as a landscape of ephemeral and fragmented encounters, is a direct testament to the magazine’s legacy. His focus on street photography as an intuitive and visceral act, rather than a mere record, aligns perfectly with Provoke’s principles.

The magazine’s influence can also be seen in the general rise of experimental street photography in Japan and elsewhere. Numerous young photographers, inspired by Provoke’s freedom and radicalism, adopted similar styles, exploring the city through a subjective and unpolished lens. The magazine legitimized a way of photography that was raw, personal, and deeply expressive, opening the door to a diversity of voices and approaches that would previously have been considered «incorrect» or «amateur» by dominant norms. Provoke not only changed what was photographed, but also how it was photographed and, crucially, how photography itself was understood and valued.

In short, Provoke represented a decisive turning point in the history of photography. By challenging established norms and introducing a radically new visual and conceptual vocabulary, the magazine paved the way for new and diverse forms of visual expression. Its impact resonates to this day, reminding us that photography is not only a mirror of reality, but also a powerful tool for reflection, critique, and the expression of human experience in all its complexity and ambiguity.

Provoke magazine, despite its short-lived editorial presence, was a beacon of the Japanese photographic avant-garde, leaving a legacy that resonates to this day. Its emergence onto the art scene in the late 1960s marked a bold break with postwar photographic conventions, dominated by documentary realism and the pursuit of an objectivity that Provoke’s founders considered insufficient to capture the tumultuous reality of their time. The «Are, Bure, Bokeh» aesthetic—rough, blurred, and out of focus—was not merely a technique, but a philosophical statement reflecting the subjectivity and uncertainty of an era of profound social and political upheaval.

Books and Exhibition Catalogs

Provoke: Between Protest and Performance: Photography in Japan 1960–1975 (Edited by Matthew Witkovsky, Diane Dufour, and Duncan Forbes).

This is probably the most comprehensive and definitive resource on Provoke and the broader context of Japanese avant-garde photography during that period. It contains critical essays by several experts and a vast selection of images. If you could only choose one book, this would be it.

Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and 1970s (Aperture, edited by Ryūichi Kaneko and Manfred Heiting).

While not focused exclusively on Provoke, this book is essential for understanding the photobook phenomenon in Japan, a key format for Provoke artists and their generation. It shows the context in which Provoke was embedded and how its members, especially Moriyama and Nakahira, explored the photobook as an extension of their practice.

For a Language to Come by Takuma Nakahira.

This is Nakahira’s seminal photobook, published shortly after Provoke. It is a visual manifestation of his post-Provoke ideas and his search for a new photographic language. Reading about this book and its implications is crucial to understanding the evolution of the thinking of one of the founding fathers.

Bye Bye Photography by Daidō Moriyama.

Another iconic photobook that showcases the continuity and evolution of the «Are, Bure, Bokeh» aesthetic in Moriyama’s work. It is an even more radical exploration of fragmentation and subjectivity in photography.

Daido Moriyama

Koji Taki

Takuma Nakahira

Yutaka Takanashi

Deja un comentario