The History of Photojournalism

From its origins in the 19th century to the digital age and artificial intelligence, photojournalism has been an essential tool for documenting history, denouncing injustices, and emotionally connecting people with world events. This discipline, which combines aesthetic sensitivity with a pressing need for information, has allowed photography to become not only an art form, but also an irrefutable witness to reality. Over more than 170 years, photojournalism has evolved with technology and society, adapting to new platforms, ethical challenges, and cultural contexts.

Origins of Photojournalism (1850s-1880s)

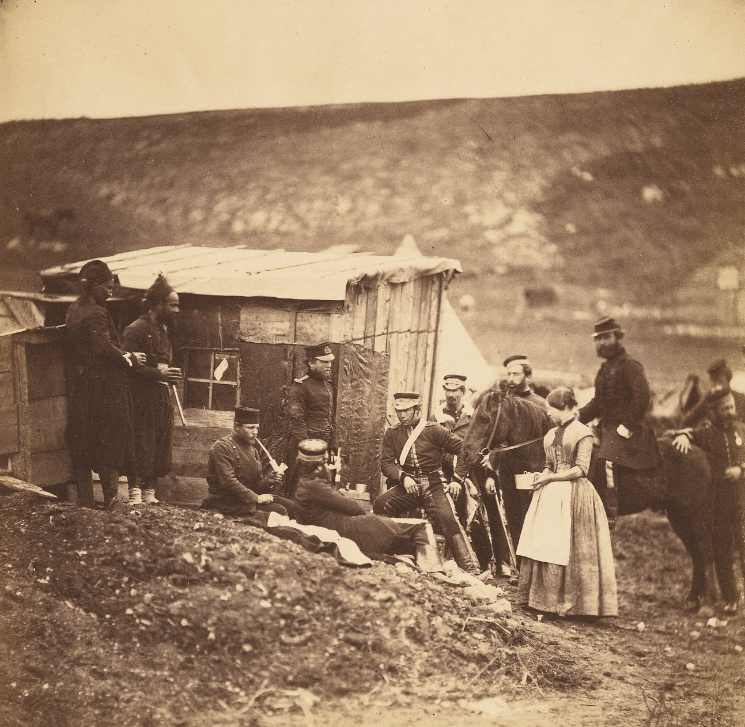

The birth of photojournalism can be traced back to the Crimean War (1855), when Roger Fenton was sent by the British government to document the conflict. Although his images avoided explicit violence for political reasons, they were a milestone in establishing photography as a means of reporting in war contexts. Shortly after, Mathew Brady organized a team of photographers, including Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, to cover the American Civil War (1861-1865). These photographers offered shocking images of corpses on the battlefield, trenches, and military encampments. The brutality depicted in these images transformed the way the public understood war.

Being a still-nascent technology, the cameras of the time required long exposure times and delicate transport. Even so, photographers traveled with portable laboratories. Their work, although limited in immediate circulation, was disseminated in exhibitions and illustrated publications, and served as a precursor to the testimonial function of photography.

Roger Fenton, 1855

Social Photography and the Moral Mission (1880s-1920s)

At the end of the 19th century, photography became a tool to expose social inequalities. In the United States, Jacob Riis used the camera to document the inhumane conditions in New York’s slums, especially on the Lower East Side. His book How the Other Half Lives (1890) became a powerful denunciation that prompted urban and sanitary reforms.

Lewis Hine, for his part, focused on child labor. He toured factories, mines, and agricultural fields, capturing images of children in extreme labor situations. His visual work was key to the passage of stricter labor laws. Hine exemplified how photography could transcend art to become an instrument of social justice.

During this period, publications also emerged that integrated photographic images with journalistic text, consolidating the visual reportage format. Illustrated magazines began to include photographs as an essential part of their reporting.

Jacob Riis, 1890

Lewis Hine, 1908

Consolidation of Modern Photojournalism (1930s-1950s)

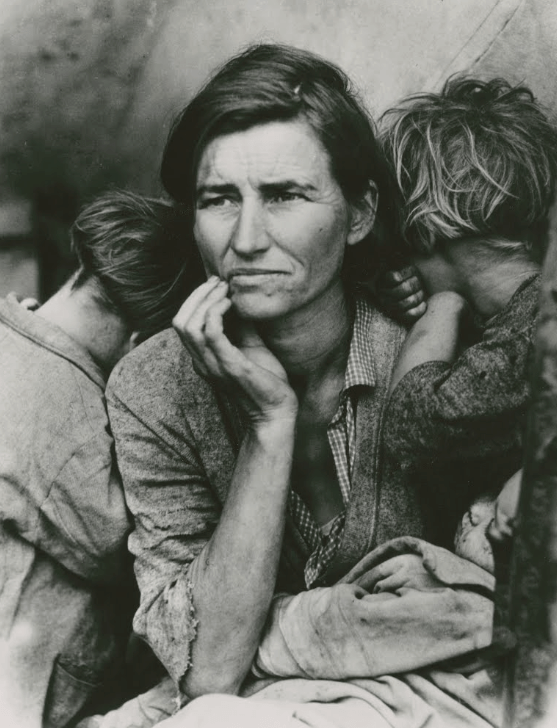

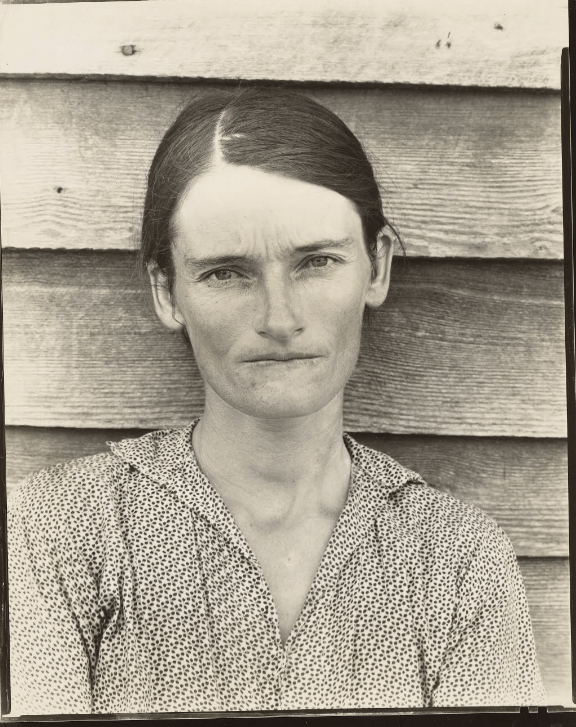

The Great Depression in the United States and the rise of fascism in Europe ushered in a period in which photojournalism reached its peak. The creation of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) promoted a social documentation program where photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Arthur Rothstein captured the impact of the economic crisis on rural areas. Images such as Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936) became icons of human resilience.

Dorothea Lange, 1936

Walker Evans, 1936

Arthur Rothstein, 1937

In Europe, with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Robert Capa emerged as one of the great names in war photojournalism. His famous photograph Death of a Militiaman (1936) captured the drama of a conflict that ideologically polarized the world. Capa, along with Gerda Taro and Chim (David Seymour), would later found the Magnum agency, a pioneer in defending photographers’ copyright.

Robert Capa, 1936

During World War II, magazines such as Life and Picture Post published visual reports that kept the public informed. W. Eugene Smith produced famous coverage from the Pacific, showcasing not only the conflict but also the humanity of the combatants. In this context, Henri Cartier-Bresson developed his style centered on the «decisive moment,» capturing spontaneous moments charged with visual meaning.

Henri Cartier Bresson, Italy, 1937

Visual Revolution and Ethical Questioning (1960s-1980s)

In the second half of the 20th century, photojournalism was transformed by social struggles, decolonization, and the Vietnam War. It was a period of political ferment and technological advances that allowed for greater portability and speed in photographic production.

Don McCullin captured the brutality of the conflict in Vietnam and Northern Ireland. His images reflect both the violence and the dignity of those who suffer it. Meanwhile, James Nachtwey emerged with a deeply empathetic vision, focused on the victims of war and famine.

Don McCullin, 1964

James Nachtwey, 1993

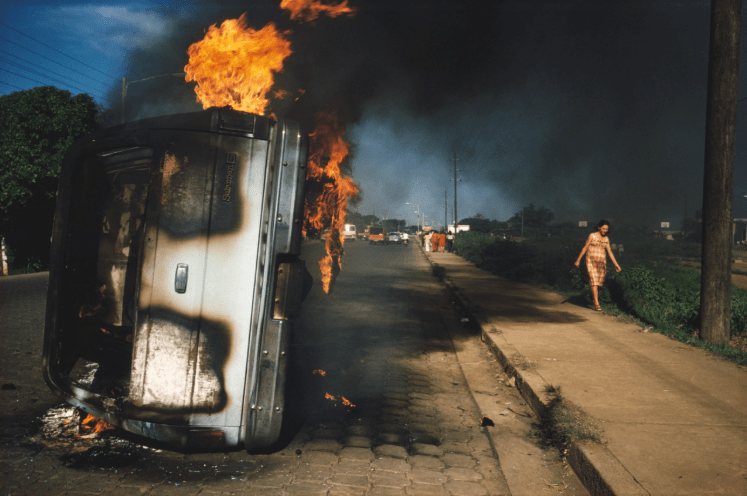

Photojournalism also began to question its role: Can a photographer be neutral in the face of suffering? To what extent is it ethical to document tragedy without intervening? These questions gave rise to a critical awareness within the profession. Susan Meiselas photographed the revolution in Nicaragua from an unusual closeness, becoming emotionally involved with her subjects. The images began to show not only the event, but also the context and emotion.

Furthermore, illustrated magazines began to lose influence in the face of television, which motivated photojournalists to seek new ways of telling stories, including photo books and solo exhibitions.

Susan Meiselas, Nicaragua

Digitalization and New Scenarios (1990s-2000s)

The emergence of digital photography completely changed the game. Digital cameras allowed for greater immediacy, in-field editing, and remote image sharing. Digital media emerged, and traditional agencies like Magnum and VII Photo Agency evolved toward multimedia platforms.

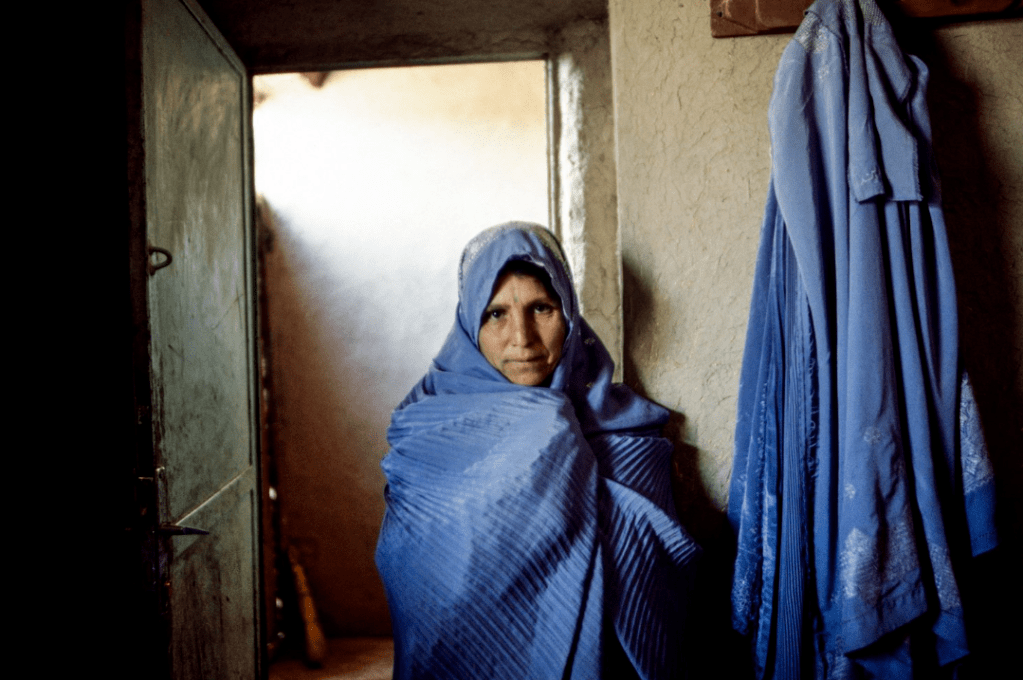

During this period, photographers such as Lynsey Addario, Joao Silva, and Ron Haviv covered conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Balkans, and Sudan. Rapid image delivery was key to informing the world in near real time, but it also brought with it new challenges: accuracy, digital manipulation, and content saturation.

Humanitarian photography also gained ground. Paul Nicklen began documenting climate change in the Arctic with a focus both scientifically and emotionally. At the same time, the NGO World Press Photo grew in prestige, awarding works of high social and visual impact each year.

Lynsey Addario, Afganistan, 2000

Participatory Photojournalism and Social Media (2010s)

The rise of smartphones and social media transformed any citizen into a potential photojournalist. Protests such as the Arab Spring (2010-2012) were widely documented by activists and civil society. This new dynamic decentralized photojournalism and placed the discussion on curation, verification, and image rights at the center.

Projects such as Everyday Africa, initiated by Peter DiCampo and Austin Merrill, showcased everyday life in Africa beyond the narrative of conflict. In parallel, platforms such as Women Photograph and Native Agency promoted the inclusion of women and photographers from historically marginalized communities.

Contemporary Challenges and the Future of Photojournalism (2020s)

Photojournalism is currently facing a crossroads. Artificial intelligence can generate high-quality fake images, which has led to the creation of verification tools like PhotoDNA and initiatives like the Content Authenticity Initiative. There is also growing concern about the labor rights of photojournalists, who often work as freelancers in precarious conditions.

The use of algorithms on social media determines which images go viral, which can distort the global perception of a crisis. The need for an ethical approach is more urgent than ever: protecting the dignity of those portrayed, avoiding re-victimization, and prioritizing informed consent.

Despite these challenges, photojournalism remains a key element of democracy. Contemporary examples such as Ivor Prickett’s reports on the war in Syria, or Emilio Morenatti’s images from Ukraine, demonstrate that photography maintains its narrative and empathetic power. Organizations such as The Everyday Projects, the International Center of Photography, and World Press Photo continue to train and honor new generations.

Recommended books to delve deeper into photojournalism

«On This Site: Landscape in Memoriam» – Joel Sternfeld. A visual reflection on memory, history, and violence in the United States.

«Magnum Contact Sheets» – ed. Kristen Lubben. A unique look at the working process of Magnum’s great photographers.

«Photojournalism: The Professionals’ Approach» – Kenneth Kobre. A classic handbook on the theory, technique, and ethics of photojournalism.

«Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History» – Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub. Although not focused solely on photography, it is key to understanding the testimonial value of the image.

«War Is Beautiful» – David Shields. A visual critique of the way the American media has portrayed war.

«The Bang-Bang Club» – Greg Marinovich and João Silva. An autobiographical account of four photojournalists in South Africa during apartheid.

«Susan Meiselas: Mediations» – Mapfre Foundation. An overview of Meiselas’s work and her commitment to participatory photography.

«Witness in Our Time: Working Lives of Documentary Photographers» – Ken Light. Interviews and testimonials from leading contemporary photographers.

Deja un comentario